What makes a character unforgettable? A classic novel provides a handful of critical answers

A distant husband, father to two flighty children. A businessman with dubious ethics. A Loyal friend. A man who longs for a life with greater meaning than an existence he finds increasingly empty.

He could be someone’s father, uncle, husband, brother, a memorably flawed human being.

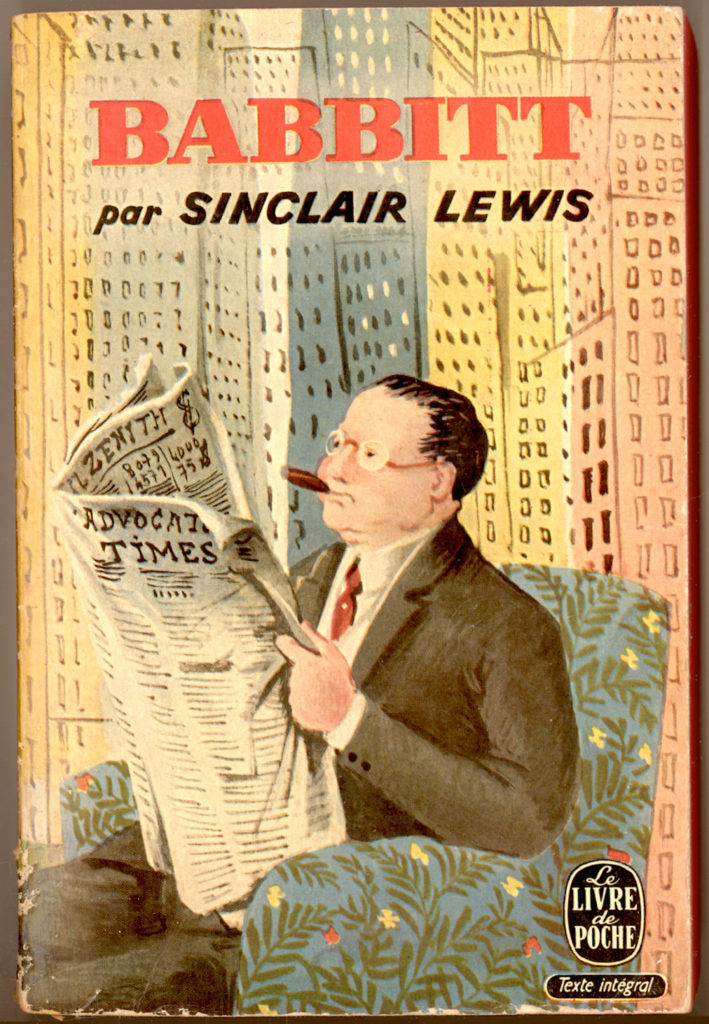

But he is actually a character, George F. Babbit, a figment of a writer’s imagination, in this case, that of Sinclair Lewis, who wrote a series of closely-observed satirical novels that won him the Pulitzer and Nobel Prizes.

I first read his 1922 novel, “Babbitt” in high school and have returned to it many times since. It’s been literature as comfort food. “Babbit” is nearly a century old and admittedly outdated in many, ways, but it remains a classic of literary realism.

Although he wrote fiction, Lewis brought to his novels a journalist’s attention to detail while researching his novels. From it, I learned many things, about style and satire and America in the early 20th century.

But most of all, Babbit teaches valuable lessons on how to create a believable character, so vivid that I can tell you, even though I haven’t cracked its pages in several years, what happens to him over the course of several months that constitute the novel’s trajectory. How he:

- embraces a boosterish, patriotic and xenophobic middle-class business community

- gleefully rips of clients and his employees

- Ignores and cheats on his long-suffering wife

- comes to doubt and ultimately doubt his beliefs and existence;

- engages in a misguided and humiliating affair and then, chastened by ostracism, renews his tragic allegiance to his culture and community.

How did Lewis create a narcissistic character that lingers so deeply in the mind? And what can writers of fiction and narrative nonfiction learn from his methods that they can bring to their own stories?

How did Lewis manage to create a character, on one hand, an odious human being, while at the same time, as English novelist Hugh Walpole wrote, “without extenuating one of his follies, his sentimentalities, his snobbishness, his lies and his meannesses, he has made him of common clay with ourselves.” Babbitt, the man and the novel, are a triumph of the imagination and the writerly gifts of his creator.

Strong characters are a mosaic of many features. Here are five principal ways, with examples from my Kindle edition of “Babbitt”, that Lewis relies on to create a believable figure. (You can read the book for free courtesy of Project Gutenberg.)

- Physical description

- Status details

- Dialogue

- Action

- Primary goal

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

What a character looks like creates a mental picture in the reader’s eye. Otherwise, he is a cipher. Lewis introduces Babbit in the opening pages as he sleeps:

He was forty-six years old now, in April, 1920, and he made nothing in particular, neither butter nor shoes nor poetry, but he was nimble in the calling of selling houses for more than people could afford to pay. His large head was pink, his brown hair thin and dry. His face was babyish in slumber, despite his wrinkles and the red spectacle-dents on the slopes of his nose. He was not fat but he was exceedingly well fed; his cheeks were pads, and the unroughened hand which lay helpless upon the khaki-colored blanket was slightly puffy. He seemed prosperous, extremely married and unromantic;

What does my character look like, sound like, smell like? Will readers be able to visualize him or her?

STATUS DETAILS

Status details are realistic and revelatory items that bring characters to life in fiction and creative nonfiction. In The New Journalism, Tom Wolfe defines status details as:

“the recording of everyday gestures, habits, manners, customs, styles of furniture, clothing, decoration, styles of traveling, eating, keeping house, modes of behavior toward children, servants, superiors, inferiors, peers, plus the various looks, glances, poses, styles of walking and other symbolic details that might exist within a scene. Symbolic of what? Symbolic, generally, of people’s status life, using that term in the broad sense of the entire pattern and behavior and possessions through which people express their position in the world or what they think it is or what they hope it to be. The recording of such details is not mere embroidery in prose. It lies as close to the center of the power of realism as any other device in literature.”

For Babbit, the details are the contents of his pockets, totems of his career and station in life.

He was earnest about these objects. They were of eternal importance, like baseball or the Republican Party. They included a fountain pen and a silver pencil (always lacking a supply of new leads) which belonged in the righthand upper vest pocket. Without them he would have felt naked. On his watch-chain were a gold penknife, silver cigar-cutter, seven keys (the use of two of which he had forgotten), and incidentally a good watch. Depending from the chain was a large, yellowish elk’s-tooth-proclamation of his membership in the Brotherly and Protective Order of Elks. Most significant of all was his loose-leaf pocket note-book, that modern and efficient note-book which contained the addresses of people whom he had forgotten, prudent memoranda of postal money-orders which had reached their destinations months ago, stamps which had lost their mucilage, clippings of verses by T. Cholmondeley Frink and of the newspaper editorials from which Babbitt got his opinions and his polysyllables, notes to be sure and do things which he did not intend to do,

…But he had no cigarette-case. No one had ever happened to give him one, so he hadn’t the habit, and people who carried cigarette-cases he regarded as effeminate.

What status details are evident in my character’s life; from the car she drives to the contents of his wallet? What do they reveal about her?

DIALOGUE

How people speak to others and past them and to themselves within scenes reveals their character. In this exchange with his wife, we hear the kind of blustery monologue that characterizes Babbitt’s solipsistic personality and witness a Man Child on full display.

“I feel kind of punk this morning,” he said. “I think I had too much dinner last evening. You oughtn’t to serve those heavy banana fritters.”

“But you asked me to have some.”

“I know, but—I tell you, when a fellow gets past forty he has to look after his digestion. There’s a lot of fellows that don’t take proper care of themselves. I tell you at forty a man’s a fool or his doctor—I mean, his own doctor. Folks don’t give enough attention to this matter of dieting. Now I think—Course a man ought to have a good meal after the day’s work, but it would be a good thing for both of us if we took lighter lunches.”

“But Georgie, here at home I always do have a light lunch.”

“Mean to imply I make a hog of myself, eating down-town? Yes, sure! You’d have a swell time if you had to eat the truck that new steward hands out to us at the Athletic Club! But I certainly do feel out of sorts, this morning. Funny, got a pain down here on the left side—but no, that wouldn’t be appendicitis, would it? Last night, when I was driving over to Verg Gunch’s, I felt a pain in my stomach, too. Right here it was—kind of a sharp shooting pain. I—Where’d that dime go to? Why don’t you serve more prunes at breakfast? Of course I eat an apple every evening—an apple a day keeps the doctor away—but still, you ought to have more prunes, and not all these fancy doodads.”

“The last time I had prunes you didn’t eat them.”

“Well, I didn’t feel like eating ’em, I suppose. Matter of fact, I think I did eat some of ’em. Anyway—I tell you it’s mighty important to—I was saying to Verg Gunch, just last evening, most people don’t take sufficient care of their diges—”

His speech also reveals his cultural and social influences in the manly but cartoonish banter with his friends over lunch at the Zenith Athletic Club.

“Oh, boy! Some head! That was a regular party you threw, Verg! Hope you haven’t forgotten I took that last cute little jack-pot!” Babbitt bellowed. (He was three feet from Gunch.)

It unveils his needs and desires in his pathetic attempts to woo a neighbor at a dinner party.

“Anybody ever tell you your hands are awful pretty?”

What does my character talk like? What does the way he talks to others reveal about him or her?

ACTION

Babbit is a series of set pieces, built on scenes that show Babbit in action. A boisterous lunch at his club. A boozy convention with a disastrous visit to a brothel. A fishing trip in the Canadian woods with his best friend, the reticent and artistic Paul Riesling. A bitter labor dispute in which he inadvisedly takes the side of the workers. His dealings with real estate clients. His brief love affair with a widow and his involvement with her alcohol-sodden friends. They show Babbit’s likes and dislikes, his interactions with other characters and his goals in life.

How do my characters behave? How do their actions drive the plot and reflect the theme?

PRIMARY GOAL

More than anything, Babbit wants to belong, to be part of a community that embraces and admires him even as he desires another life that enables him to be free of his family, his companions and his work. But even when he rebels, his actions and those of others thwart those desires. He cheats on his wife only to feel trapped by that illicit relationship as he is in his sexless marriage. He befriends a Socialist in a labor dispute, betraying his class in a final act of rebellion which causes his friends and fellow Boosters to reject him. It is only after his wife falls seriously ill that his friends rally round him. Defeated, he rejoins their company, rejecting his dream life. The tragedy is complete.

What does my character want more than anything in life? Wealth? Respect? Victory? Love?

That goal will play into everything we learn about the character.

I could have chosen other examples from my bookshelves and among the movies I’ve seen with equally memorable characters.

The quirky obsessed comic industry creators in Michael Chabon’s best-selling and Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay.”

Feisty Erin Brockovich in the eponymous Academy Award-winning film about a lowly legal clerk who takes down a polluting corporation.

Mitchell Stephens, the haunted lawyer in Russell Banks’ “The Sweet Hereafter,” a novel set in a small town reeling from a school bus accident that has killed most of its children.

The brutally up-and-down boxer Floyd Patterson in Gay Talese’s classic profile, “The Loser.”

John Updike’s “Rabbit,” a series of 20th-century novels about a car salesman whose realistic approach and themes echo the life of Babbit.

For that matter, I could have chosen from Lewis’ other novels: “Main Street,” his breakthrough novel about an idealistic young woman suffocated in a narrow-minded village; “Arrowsmith,” about an idealistic scientist,” or “Elmer Gantry,” which eviscerated a huckster evangelist. All are triumphs.

But I chose Babbit, not only because I am so familiar with him, but because I wanted to know why he is so unforgettable so that I can develop characters as memorable as those Lewis created.

Since writers read twice—once to enjoy, the other learn—dissecting one of your favorite books or stories as I did can be a valuable exercise. If you want to create a memorable character, study how one is made.

Craft Query: Who are the most memorable characters you have encountered in fiction or nonfiction and what made them linger in your mind.?

May the writing go well!

..