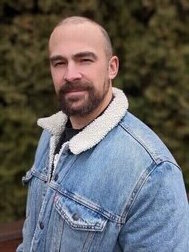

Brendan O’Meara is the host/founder/producer of The Creative Nonfiction Podcast, now in its ninth year, where he talks to people about the art and craft of telling true stories. He also produces Casualty of Words, a daily micropodcast for people in a hurry. He is an award-winning features writer, newspaper opinion page editor (until he will inevitably get laid off), founder of podcast maker Exit 3 Media, and author Six Weeks in Saratoga: How Three-Year-Old Filly Rachel Alexandra Beat the Boys and Became Horse of the Year. He’s wrapping up a memoir on his father and baseball called The Tools of Ignorance. He lives in Eugene, Oregon.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

I don’t think it can be understated that, One, there is no unilateral path through this morass and Two, knowing that, run your own race, embrace your own path, celebrate your path.

I got myself into a lot of “trouble” by thinking there was a singular path to writing fame and prestige and notoriety. It led me down a toxic path of jealousy, envy, bitterness, and resentment that was compounded by the insidious rise of social media. “That person is doing what I want to do and here I am selling running shoes, writing slideshows (Winners and Losers from the Daytona 500 for $50) and he’s got a 3,000-word profile in Outside and he’s my age or younger and what the hell am I doing wrong and I bet he isn’t writing these terrible slideshows or stacking produce at Whole Foods and certainly Wright Thompson or Susan Orlean never had to do this. So if I was really ANY good at this, then why am I landscaping and doing reporting calls on my lunch break? Surely my heroes and peers weren’t doing this, right?

When my first book came out, the book deal came as a result of fitting a woman for shoes who knew an editor at the press who published the book.

Another job I had, doing calls on lunch breaks, won an award for this piece. basically while dirty from cleaning up hedges all day in Jersey City.

What you realize, often after a long, long, long time is that you can’t know someone’s privilege or the lucky break or the sheer titanic and singular focus others might possess. Or, more likely, they are doing unglamorous work to pay the bills (ghost writing, content marketing, maybe a day job at Trader Joe’s) and they don’t post that on Instagram. All you see is the veneer of non-stop winning.

By stopping with the comparison game, and celebrating other people’s work as much or more than your own, you’ll find your time will come and someone else will look at you and think, “It looks like they’ve been there the entire time.”

There are more 10 and 15-year overnight success stories out there than you realize. In a culture that values precocity and youth above the grind and experience, run your own race and avoid 30-Under-30 lists like COVID.

What has been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

This might be a controversial statement but I’ll say it anyway as a double major in college and someone who earned an MFA in 2008: college doesn’t matter. A body of work matters.

Any job I have ever gotten was based on life experience and the body of work I amassed by showing up every day, drip by drip. Here, I made this.

I’m mentoring an 18-year-old high school grad. She’s very bright, is not enrolled in college, and by happenstance our paths crossed (she emailed a bunch of newspaper editors here in Eugene and I was the only one who responded to her). I’m working with her to build a body of work she can show clients or potential employers or editors because when you pitch an editor a feature, they never, never, never ask you where you went to school. They ask for your clips and whether you can deliver on what you’re promising.

College has a purpose, but make no mistake: unless you’re studying to cut open human bodies, higher education has more in common with high school only with more drinking. Why accrue the debt if you can just do the work?

If you had to choose a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be and why?

I write about horse racing quite a bit and there are horses who are plodders, who are slow out of the gate, trail the field, conserve energy, save ground, and do most of their damage (See Zenyata… “This! Is! Un! Be! Lievable!)–if they do any damage at all–late in the race. They let the “rabbits” and “speed balls” set blistering paces on the front end, wait for them to tire, then surge from the back of the herd. This echoes one of my favorite quotes from the run of The Creative Nonfiction Podcast when I first spoke with Pulitzer Prize finalist Elizabeth Rush, “I’m just a mule. I just show up every day and climb very, very slowly up that mountain.”

I’ve always been a bit of a late bloomer, one who has been frustrated by the precocious around me (which makes me bloom even later since I waste too much of time worrying about things outside of my control) and a culture that puts a premium on the precocious at the expense of those with more experience, those who need more time to hit their stride, or those who don’t reach exit velocity until they’re in their 40s or even 50s. Maybe older.

What’s the single best piece of writing advice anyone ever gave you?

“Don’t get writerly on me, Brendan.”

In the memoir I’m wrapping up, “The Tools of Ignorance: A Memoir of My Father and Baseball,” I’d have what I thought were nice painterly flourishes or pyrotechnic language befitting of a David Foster Wallace wannabe. [Note to wannabes of any ilk: There’s already a [FILL IN THE BLANK]. We need [YOUR NAME HERE].

Prose doesn’t have to be lyrical or pretty to be artful. My editor telling me “Don’t get writerly” was saying me this: Surrender to the story. Tell the story straight. Get out of the way. Let the story be a warm bath you can sink into (Dammit! See?! I’m getting writerly!).

When you lock into the story, do your best to get out of its way and let it do the heavy lifting. The truth and relatability of the story will carry the reader.

There are stylists out there, but odds are you’re not Jimi Hendrix or Miles Davis or Wes Anderson. Do your best to fade into the background so the reader almost has no idea how they got from page 1 to page 324.