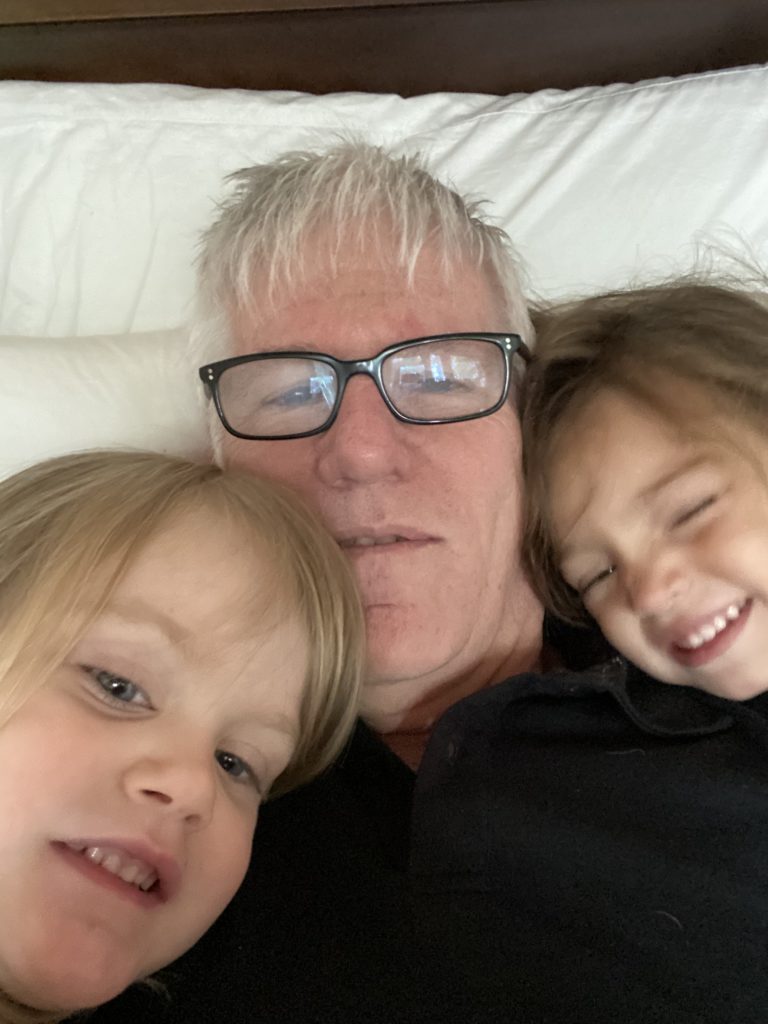

Thomas French with his daughters Brookie and Greysi

Thomas French teaches journalism at Indiana University. For nearly three decades before, French worked as a narrative project reporter at the St. Petersburg Times/Tampa Bay Times, specializing in serialized storytelling. Angels & Demons, a story about the murders of a mother and her two teen daughters while visiting Florida, earned him a Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 1998. French is also the author of four nonfiction books. Most recently, he and his wife Kelley co-authored Juniper, a book about the premature birth of their oldest daughter.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

I’ve learned so many things over the years. I’ve come to believe that one of the greatest things about being a journalist is that it asks you to keep learning something new all the time, every day. I guess the single most important lesson has been the realization that meaning lies everywhere around us and within us.

One time I asked a subject of mine – a self-taught scholar of many disciplines — what she liked to read for her own enjoyment. Her 12-year-old son, listening to the interview, blurted out, “She reads puppy books.” I asked what a puppy book was, and the boy grabbed a worn and dog-eared romance novel off the shelf — The Golden Barbarian, with the cover showing a young maiden melting in the arms of the aforementioned savage —- and said, “You know, they fall in love, they get married, they have puppies.” Then he handed me the book with a knowing grin and said, “Check out page 192.”

I loved that this brilliant woman’s 12-year-old son knew where the dirty parts were in her romance novels. It was one of those details so beautiful that I knew right away it would end up in my final draft. But it wasn’t until much further down the road, after this woman ended her marriage and decided to raise their five children on their own — all because she was sure that there was another man waiting for her, a man better suited for her — that I realized I had missed the meaning of this woman’s devotion to her puppy books. She was lonely. She did not believe that the man beside her understood her or truly knew her or was right for her. She wanted to find someone who would love her the way she deserved, and by God, she found him not long afterwards and married him and moved with him and the kids to a big house in France.

The mystery of who this woman was and what she truly wanted had been in front of me the whole time, hidden inside The Golden Barbarian. And I had missed it. I had overlooked all of these big things waiting inside this little detail.

It was just another reminder, one of hundreds over the years, that I need to pay attention to everything and look for the meaning hidden right in front of me.

What has been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

Okay, so I read this passage once in The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, Roberto Calasso’s astonishing retelling and reframing of Greek mythology. It was an insight the writer had about the multiple versions of each myth and all the heroes and gods and goddesses.

“Mythical figures live many lives, die many deaths,” Calasso wrote. “But in each of these lives and deaths all the others are present, and we can hear their echo.”

Those lines hit me like a thunderbolt. I was about 35 at the time, and I knew that in those few decades I had already lived several lives and had already died and been reborn several times. And if that was true of me, then it had to be true of all of us, not just mythical figures, but the human beings whose stories I was trying to chronicle. And when all of this washed through me, I realized I had a lot more digging to do in my reporting. Because up until then, I hadn’t recognized the multiplicity of each person’s experiences. I hadn’t seen it, because I hadn’t known to look for it, and once I did learn it, my reporting instantly went deeper.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be and why?

Wow. On my better days, I guess I’d compare myself to someone who digs, a miner maybe. Anne Hull once scribbled me a note on a piece of scrap paper and gave me some advice that I’ve held onto tightly ever since. I hope she’ll forgive me for sharing it: Don’t turn back. Understatement. Insight. The scalpel. Tool into the past without misty eyes but with the compass and charts of an explorer. Tunnel there . . . As the boys in Princeton, W.V. say: Get dirty, brother.

What is the best piece of writing advice anyone ever gave you?

I’ve been extremely lucky in my writing life to have learned from so many great journalists. The best advice I ever received — and I received it from many — is the same advice I give myself every time on deadline and the advice I give every writer I work with, whether they’re doing a quick daily or burrowing inside a massive book.

“Keep going.”