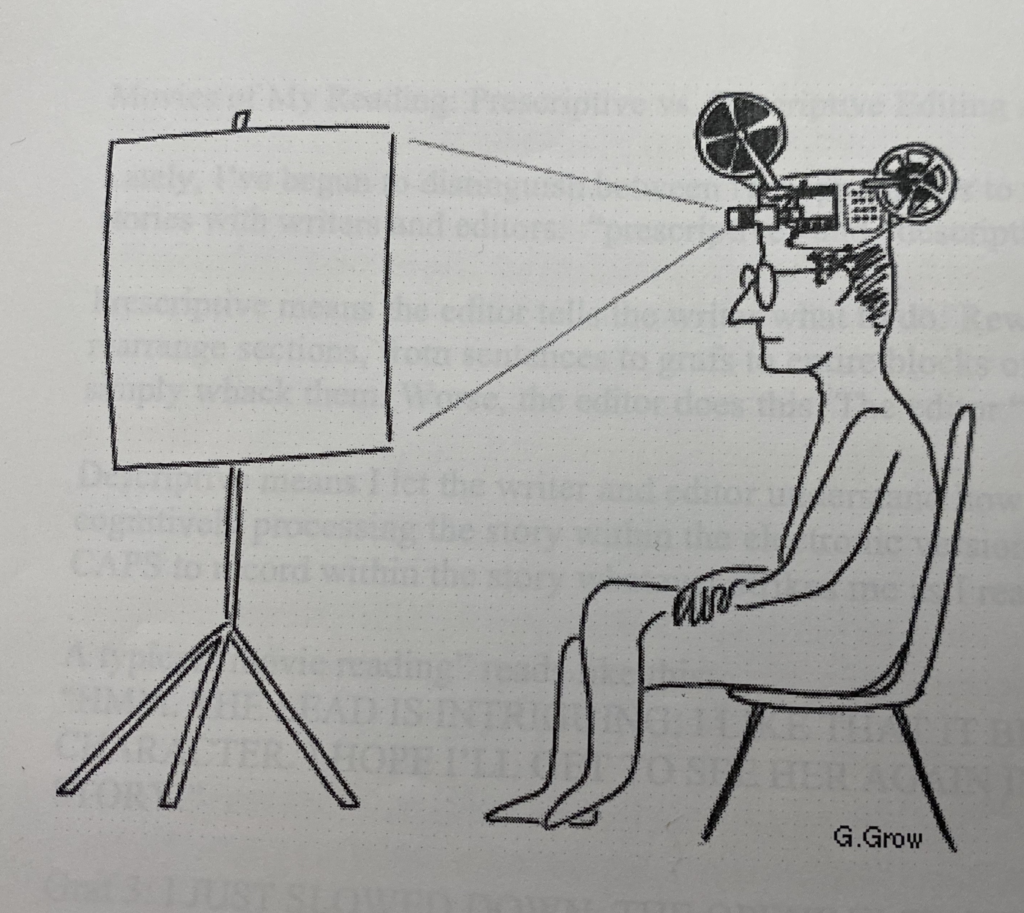

Writing teacher Peter Elbow says that what writers need is “not advice about what changes to make or theories of what is good and bad writing,” but “movies of people’s minds while they read your words.”

Inspired by that philosophy, I tell writers I coach that rather than critique their stories I will give them a “movie of my reading.”

Such a reading is a highly subjective, but factual commentary that attempts to reproduce the way I process a story and try to help the writer achieve their goals.

A typical “movie reading” is embedded in a draft or revision of a story. Think of it as a real-time edit without the red pencil wielded by editors who want to fix your copy rather than enable you to do so through coaching. Here’s an example of what you’ll find:

“Hmm. What’s this story about? The lead is intriguing. I get a hint of what’s going on, and I’ll keep reading. When I get to the third graf I slow down. I’m confused. I had to go back and read that sentence twice to make sense of it. Okay, I’m back on track, but now I’m beginning to wonder what this story is about. What’s the point here? I’m getting bogged down in this section. Love this line! Hmm, that’s a great quote, but who said it? Okay, now I’m completely lost, but I’ll keep plugging away. Page two. Oh, I get it, that’s what it’s about. Gosh, why didn’t you tell me that sooner? What would you think about moving it up? What a great simile! Writers profit from using literary techniques wielded by poets and fiction writers. Can you bring this character to life, with descriptions, a scene or dialogue? Moving on, I’m really engrossed. But wait, I forgot who this person is. What about a brief descriptor to remind the reader? It’s a good ending, but what would you think of stopping the story two paragraphs earlier?”

This approach–a combination of comments and questions–is especially useful with journalists and other writers who may come to a writing conference thinking the story is done or, even if they recognize it has problems have no idea how to solve them. My “movie reading” isn’t a vague critique, (“It just doesn’t work for me.”) but instead gives the writer a detailed sense of how one reader absorbed the story. It’s hard to argue with a reader who says he’s confused. You either say, “Tough,” or “Well, I don’t want you to feel that way. How could I clear things up?” My job is to help you see problems, offer solutions and for you to make the changes that make your meaning clear and your story shine.