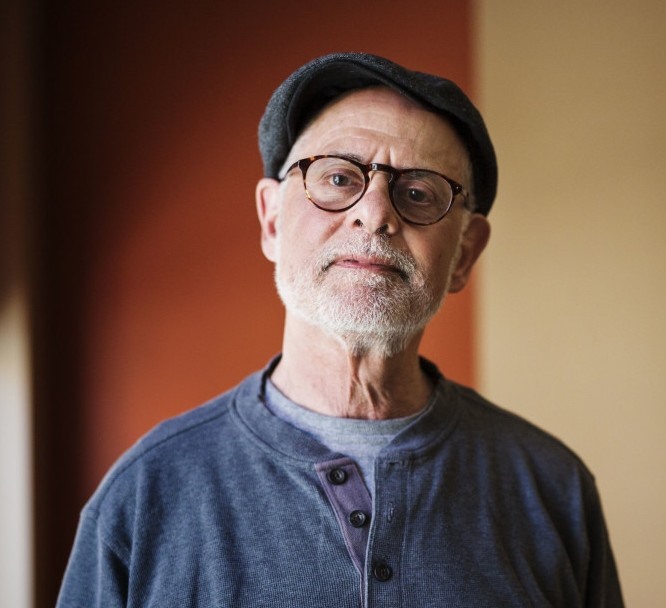

Mark Kramer is a writer, professor, and leader in the international movement to bring narrative journalism into books, magazines, documentaries, broadcasts, podcasts, and news media. He teaches an independent master class for mid-career writers with longform projects. It explores the process from topic selection through to publication, and includes fieldwork, note-coding, structuring, drafting and revising, and covers sentence-craft, voice, pace, scene-and-character portrayal, and ethics.

Kramer started America’s leading narrative nonfiction writing conference at Boston University and continued it while writer-in-residence and founding director of the Nieman Program on Narrative Jounalism at Harvard University, and then when it returned to Boston University. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Boston Globe and other papers, and in National Geographic, The Atlantic Monthly, Outside, Best American Essays, The Nation, etc.

His books include Three Farms: Making Milk, Meat and Money from the American Soil; Invasive Procedures: A Year in the World of Two Surgeons; and Travels with a Hungry Bear: A Journey to the Russian Heartland. He’s co-edited two widely-adopted textbooks–Literary Journalism; and Telling True Stories: A Writers’ Guide to Narrative Nonfiction from the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University.

Kramer was writer-in-residence and professor of journalism at BU for a decade, and writer-in-residence at Smith College for a decade before that. He’s also founded ongoing conferences in Amsterdam and Bergen, Norway, and shorter-lived conferences in Johannesburg, Lisbon, Rio and Paris. He’s finishing up a handbook for narrative journalists.

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer:

That we should be called ‘revisers’ rather than ‘writers.’ I spend perhaps one percent of my ‘writing time’ writing, in new territory, filling blank pages. The rest is revising. And almost all the enduring ‘creative’ stuff–the sentences and passages and juxtaposed scenes and ideas that still gleam when I reread them a few years later, happened while I was far into reworking text.

That said, writing that first draft, and even the scarily-messy earliest revisions, are so awful compared to how good you want a piece to turn out, that we seem destined to cling to the illusion that we already know where we’re heading and the end is nigh. What’s more true is that a piece’s true destination, where you want readers to journey toward, looms up like a mirage at sea, as we persist in revising. And then when it does, we can really start pruning and shaping more exactly, and the destination and journey toward it will refine further.

Smoothing the phrasing is just one aspect of revising. When I strengthen and tune up sentences, I’m clearing the underbrush of half-formed, twice-said and superfluous words and ideas. That’s when the curve of the reader’s consecutive experience of the piece’s scenes and argument and sequence of realizations emerges, a hospitable trail you’re clearing through the woods. “Narrative arc” is a misleading term. It’s way too heavenly an aspiration for that practical period when you’re at your workbench knowing you ought to be constructing one. “Narrative arc” sounds expert but is bewilderingly hard to anticipate. How do you build a rainbow? You need one for a good piece, but you get there by considering what practical craft steps build a good scene, animate a life-like character, tighten the next floppy sentence toward austerity. I find it helps me to ask myself repeatedly, “What should the reader experience next?” and then to work on that. If you think about how next to continue perfecting readers’ sense of ‘delightful and appropriate consecutiveness’ in their reading experience, you’ll revise effectively. This is hard.

Solid structure is what the reader needs next, and in narrative work, it doesn’t spring from an outline. Revising develops it, if you favor improving the reader’s sequential flow of immersive scenes with good characters, pointing progressively toward aspects of the topic at hand (and, occasionally, feathering in interjected ideas). And of course, the reader’s experience also improves when you make the sentences you’ve drafted ever more simple, personable and elegant, until the reader is with you, a quiet, nearly invisible, host.’ ‘Curating the reader’s sequential experience’ is an effective summary mission statement for the many chores of revising. And revising. And revising.

What should happen when the hospitably accompanied reader, after enjoying those efficiently purposeful scenes with their lifelike characters, arrives at that destination? Insight, as the elements of the narrative converge and finally drop the reader off there, is the reader’s reward. In high school and college English classes, I puzzled over the term ‘theme’ that my teachers insisted writers had in mind, like the armature around which a sculptor forms clay. The puzzling term ‘theme’ has misled many a talented writer to simplify a symphony into a monotone. Destinations of good work are nuanced. They preserve the humanness of situations intact, and don’t turn them into object lessons. And they succeed as the reader realizes things, not as the writer turns preachy and sums everything up.

First draft is merely shoveling up clay from a seam in the bed of a creek and slapping it down on the work table. Sculpting it after a first rough shaping, the work emerges, as they say, from removing what isn’t the sculpture until what’s left is, AND that’s mostly what writers do.

What has been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

The electrification stage of revision. Clearly, it takes patience bordering on endurance to report and research and sculpt your way through that first draft. Then comes the long revision period, revising the revision of your revision. You’ve immersed in your scenes, gone beyond what a deadline reporter might gain just from interviewing. You slowly, while drafting, comprehend the treasures hidden even from yourself in your field notes. Once you’ve nailed down and sharpened your selection and sequence of scenes, you’re getting there.

Then, something happens that rewards what may feel is fussy tinkering with every joint between every whole lot of words! That something is what I’ve come to think of as ‘the electrification stage’ — it’s an analogy to when you frame and sheath and roof and sheetrock a house and the unfinished rooms are recognizable, in place. In your work, the scenes are mostly in place, the characters too, and that trail leading the reader from experience to experience still has a few extra loop-de-loops, but you finally know how it works. It’s sequence from realization to realization maps in your mind. You suddenly know how to put it into place. It realizes in your mind. You suddenly can connect up the wiring you’ve installed in that house you’re building, and the lights go on. You’re not done yet. In fact, the illumination contains its own punishment–you can now see fussy little flaws and have to work far into the night, in the light you’ve created. And you can finally finish eliminating what you’d once thought essential but now you can see it’s superfluous, perhaps essential for your next piece, but not for this one. Voila: electrification draft.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer?

Please see above. I’ve got a sailor in the fog and a path-clearer on a hiking trail, a hospitable host, and a carpenter building a house and briefly, a pilot doing those loop-de-loops. I guess I write to find out what I am, metaphorically.

What is the best writing advice anyone ever gave you?

Actually, it’s a pair of . . .advices. ‘!‘ and ‘fix‘.

those were the two marks that most often showed up in the drafts returned to me by my editor, friend and mentor, Dick Todd, late and much-missed editor at the Atlantic Monthly. he’d write a minuscule check in the margin when he really, really liked something a whole lot–an idea or little interstitial joke, or even a metaphor. he was given to eloquent understatement, but so brilliantly exacting that those scant checkmarks made me feel safe and enough on the right track so that when he occasionally also inscribed the word ‘fix’ in the margins (also in tiny characters) I would realize some dumb misstep I’d made that would have remained invisible to me without his marks. the “!” showed me–in my late 20s, when i was just figuring things out–that the grace of an editor’s approving “!” was powerful in helping a writer feel safe enough to write on–or revise on. and I !!!’d a lot while working with other writers’ copy. and the “fix” showed me how fine-grained and precise was the sort of revision that a text needed before it felt like it made excellent contact with readers.