In the early 1800s, an English writer named Charles Caleb Colton published a book of aphorisms, including one still popular today: “Imitation is the sincerest of flattery.” (Added later, “form” rounds out the way we know it today.)

But for those of us trying to become better writers, imitation is more than flattery; it’s a powerful and time-honored way to master the craft. “Numerous writers — Somerset Maugham and Joan Didion come to mind — recall copying long passages verbatim from favorite writers, learning with every line,” says Stephen Koch in “The Modern Library’s Writer’s Workshop: A Guide to the Craft of Fiction.”

Over the years, I’ve learned important lessons by copying out lines, passages, even entire stories by other writers whose work I admire and would like to emulate.

Typing Wall Street Journal features taught me the anatomy of a nut graf, that section of context high up in a story that tells readers what a story is about and why they should read it.

Copying word for word short stories by Larry Woiwode and Alice Adams and passages from novelists Richard Price and Stewart O’Nan taught me a variety of lessons — the evocative power of olfactory details, for instance — about the art of fiction that writers in any form can profit by using.

But a freelance magazine writing experience more than a decade ago made me a believer in a practice I’ve come to call “modeling lessons.”

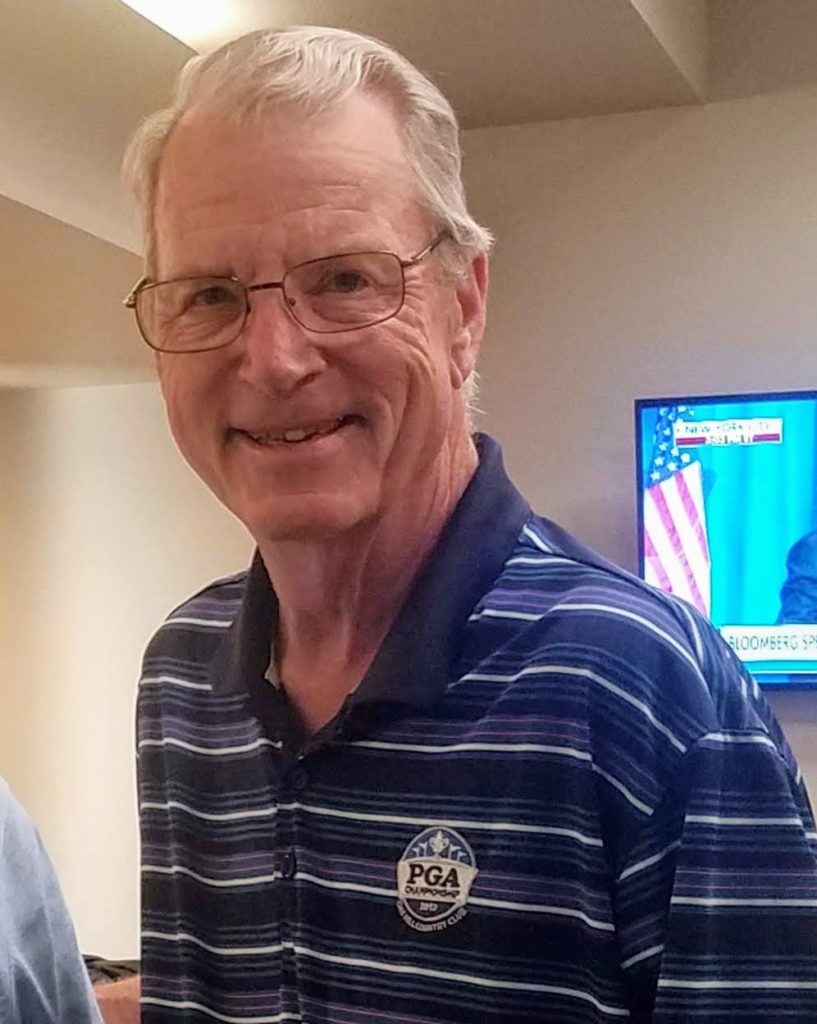

It was a dream assignment. The Washington Post Magazine asked me to write a profile of the first Vietnamese graduate of West Point. Tam Minh Pham was a young man who marched with the long gray line of cadets in 1974, returning home just in time for the fall of his country and six years of imprisonment. But his American roommate never forgot him and 20 years later marshaled his classmates to cut through bureaucratic red tape and bring their buddy to America for a new life.

It didn’t take much reporting for me to decide that this was a powerful story.

But when I asked my editor about length, I was disappointed when he said to keep it to about 2,000 words because the piece had been slotted as a second feature.

I protested — it was a great cover story, full of drama and detail — but the top editor’s mind apparently was made up.

Fine, I said, but asked for back copies of the magazine and downloaded several others from a database. Back at my desk, I studied several cover pieces, but it wasn’t until I began actually copying them out that I began to understand the magazine’s formula.

As a newspaper reporter, I routinely kept my leads to a single paragraph that if not brief enough would be trimmed by a copy editor less enamored of my words than I.

But as I typed out the Post magazine leads by its cover stars (Peter Perl, Madeleine Blais, David Finkel, Walt Harrington), it was clear the rules were different.

Their leads were several grafs long, narrative scenes that consumed 500-600 words and featured a vivid main character in action in a specific place and time, the classic storytelling structure.

Typically, the nut graf that followed the Post‘s “you are there” close-up openings was, in cinematic terms, a wide-shot. Evelynne Kramer, former editor of The Boston Globe Magazine called it “opening the aperture,” a passage that gave the reader the context and background to satisfy the curiosity piqued by the lead. If the lead showed the story, the nut graf told it. But unlike my 50-75 word newspaper nut grafs, the magazine version was more expansive.

After I’d typed about a half-dozen openings of Post magazine cover stories, I figured I had the formula sussed and was ready to try my own.

In my first interview with Pham, he’d recounted an experience one night in prison that seemed to have all the ingredients of a powerful opening. Bolstered by further reporting and emulating what I’d studied, I crafted a vivid 663-word, eight paragraph lead.

Now I needed to move the camera back and give the reader a firmer grasp on what they were reading and why. I loosened my newspaper writing reins and wrote I wrote another 500 words, the longest nut graf of my life.

I reined myself in after that, trying to keep to the 2,000 word limit, and turned it in. A couple of days later, my editor called:

You need to make it longer.

Why?

Because it’s going to be the cover piece. (You can read the entire story here.)

The lesson I learned was this: you can discover your own voice by listening to other writers, and one of the best ways to listen is by copying out their words.

This practice horrifies some respected writers and teachers; write your own damn stories, they say. But if we were visual artists, would anyone look askance at visiting a museum to try and copy the paintings to see how accomplished artists used color and shadow and contrast?

I’m not talking about plagiarism. Rather, modeling is copying stories to gain a more intimate understanding of the variety of decisions that writers make to organize material, select language, and shape sentences.

But now’s a good time for my one caveat about modeling lessons: I always copy the byline at the top of the story just in case I get deluded and confuse my copying with someone else’s writing.

Properly credited, I start copying.

When something strikes me, I’ll start to record my observations:

Wow, notice how that long sentence is followed by a short, three-word one, stopping me in my tracks to pay attention. Varying sentence length is a good way to affect pace.

Rick Bragg’s quotes are rarely very long: (“I need my morning glory.”) They’re punchy and have the flavor of human speech.

See how Carol McCabe’s leads follow a pattern? (“Cold rain spattered on the sand outside the gray house where Worthe Sutherland and his wife Channie P. Sutherland live.” “The Bicentennial tourists flowed through Paul Revere’s Mall.” “Three trailer trucks growled impatiently as a frail black buggy turned onto Route 340.”) Subject-Verb-Object. Concrete nouns, vivid active verbs. I’ve got to try that.

I believe every writer, including broadcast and online writers, can profit equally from copying successful stories in their medium. They’d do well to study how the other writing elements — audio, video, interactivity — figure in.

Whomever you model, and however you do it, the point is to pay attention to what the writer is doing and what effect it has on you, the reader. Most of all, writing is about impact, and writers need to learn how to make one, using all the tools at their disposal.

“Do not fear imitation,” says Stephen Koch. “Nobody sensible pursues an imitative style as a long-term goal, but all accomplished writers know that the notion of pure originality is a childish fantasy. Up to a point, imitation is the path to discovery and essential to growth.”

In the end, you must use your own words to become the writer you want to be, but I’ve profited from learning how other writers used theirs. And I hope you can, too.