“Writing is a way of dreaming out loud, and in public; even the most noble tales, if truly told, contain within them nuggets of evidence about the teller: soft spots, blind spots, weird obsessions. Wariness about these potentially embarrassing aspects and a willingness to weed them out is a deadly practice for a writer.”

Author: chipswritinglessons_harnwk

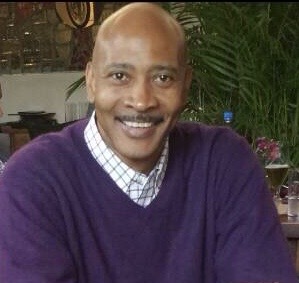

Cultivating a Sense of Wonder: Four Questions with Stephen Buckley

Interviews

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

It’s tempting to think that good writing just calls for us to stitch together the fine tips and techniques we find in newsletters like yours. The tips and techniques are awesome, but they are no substitute for thinking deeply about a piece of writing. What’s the story about? What’s the theme? What’s the focus? What’s missing? Am I being intellectually honest? What am I really trying to say? Doesn’t matter whether it’s a piece of fiction, a column, or a longform newsfeature: The deeper the thinking, the more original and compelling the writing. This takes patience, which I don’t have much of these days. So I find that I have to be savagely intentional about not cutting intellectual corners. But, in the end, that’s the only way to find my way to clarity and meaning.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

I’m going to cheat and give you two surprises: One is that cynicism kills creativity. When I was younger, I equated cynicism (which I think of skepticism poisoned by hopelessness) with sophistication. But the best writers cultivate a sense of wonder that only grows with age. It’s not that they are Pollyannas. It’s just that they see the world at odd angles, are generous and openhearted, and are always asking impertinent questions. They’ve trained themselves to be surprised. And as a result, their work gleams with beautiful simplicity and insight. The other is that writing doesn’t get any easier. After 30-plus years of writing professionally, I can’t get over how much I still have to learn. It’s like a marriage: attention must be paid. And I haven’t always paid attention to my writing. Growth is humbling—and more than a little painful sometimes. Which is why I’ve finally accepted that writers need community—virtually or in person, informal or formal. Because meaningful growth almost always occurs in community.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be?

Gosh, this one is tough. None leaps to mind. If anything, I’d say I’m an owl. I always think of owls as being the best observers and listeners in the animal kingdom (I have no idea if that’s true), and I think that’s the writer’s first duty: to take in the world as it is and then transport readers to that world. As the late James J. Kilpatrick said in The Writer’s Art: “We must look intently, and hear intently, and taste intently….” He said that’s the only path to original, precise language and images. And I agree.

What’s the single best piece of writing advice anyone ever gave you?

I got a lot of good advice over the years, but two thoughts come to mind. The first was from Roy Peter Clark, who taught me that how we order words can enhance or dilute their impact. I think about this all the time, particularly given how impatient readers are today. Their attention always feels brittle, tenuous. And so, beyond insights and clarity, I feel like I can tug them along with language that’s precise and compelling—especially at the end of a sentence or paragraph. And I often think of something John McPhee says: Writing is selection. I find this oddly liberating, especially if I’m writing a long piece. McPhee’s advice frees me to just lay everything on the screen before I go back and slash away, and reorder, whole sections. Don’t get me wrong. Selection is hard. Sometimes really hard. But it’s also fun, even exhilarating, especially when it yields writing that’s both clean and muscular.

For most of the past decade, Stephen Buckley has taught journalism, communications, and leadership in sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, the United States and Asia. He began his career with The Washington Post, where he spent 12 years as a local reporter and international correspondent, based in Nairobi and Rio de Janeiro. He later worked at the St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times), where he was a national reporter, managing editor and digital publisher before turning to teaching. Stephen served as the Dean of Faculty at the Poynter Institute and has conducted workshops at numerous writing conferences. Stephen won the International Reporting Award from the National Association of Black Journalists in 1999 for his coverage of Africa, and in 2002, the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors named him the state’s best reporter. He served as a Pulitzer Prizes juror four times. In 2015, he joined the faculty of the Aga Khan University Graduate School of Media and Communications in Nairobi where he served as an associate dean in charge of professional and executive programs. He is now a media consultant based in Nairobi.

Craft Lesson: Backstory: Using the story behind the story

Craft Lessons

“We talked all night.” “We looked up and realized the restaurant was empty.”

How often have we heard these descriptions of successful dates, those close, and perhaps apocryphal, encounters when two people reveal their personal histories to each other for the first time?

In the vocabulary of fiction, we would say they’re giving each other their backstory, revealing past actions and influences that shaped their personalities, the way they think and behave. An abusive parent? An inspiring mentor. A serious childhood illness. A painful breakup.

The literary device of backstory establishes what happens before the story that is the main plotline. It’s the information that gives characters and narrative arcs a sense of personal and social history.

Writers use them to raise the stakes for a character. Can a young mother with a history of drug abuse keep the monkey off her back so she can keep her child from the clutches of a vengeful ex-husband or Child Protective Services?

A backstory makes a character’s psychological motivations understandable. In Charles Dickens’ “Great Expectations,” why does the wealthy spinster Miss Havisham always wear her wedding dress even after it’s tattered? Why does she leave the uneaten wedding breakfast and cake untouched on a table? Because in her youth, she was left at the altar, leaving her wounded and cynical. That’s her tragic backstory, and explains why she torments Pip, the protagonist of the novel, and Estella, the orphan she adopted. She had intended to spare her ward from the suffering she endured, but couldn’t resist causing her pain.

“My dear!” she tells Pip, “Believe this: when she first came, I meant to save her from misery like my own. At first I meant no more. But as she grew, and promised to be very beautiful, I gradually did worse, and with my praises, and with my jewels, and with my teachings, and with this figure of myself always before her a warning to back and point my lessons, I stole her heart away and put ice in its place.”

Backstories are critical elements in a novel or screenplay although they should not dominate the front story which make up the scenes and exposition of the main action.

A back story has two purposes,” writer Jessica Morrell says in her article, “What Backstory Can Do For Your Story.” “A character’s backstory comprises all the data of his history, revealing how he became who he is, and why he acts as he does and thinks as he thinks. It also reveals influences of an era, family history, and world events (such as wars) that affect the story and its inhabitants.”

The writer needs to know each character’s backstory, even though they may reveal only a small percentage. Lives are long. Just as people don’t tell a new friend or lover every single thing about themselves during a first meeting, the effective writer parcels out the backstory judiciously rather than cramming them all in flashbacks that tear the reader from the main story that has grabbed their attention in the first place.

There are a variety of ways to introduce backstory, including flashbacks, exposition, dialogue, direct narration and a character’s recollections. Whatever method you choose, avoid dumping background information on the story all at once.

“The most important things to remember about backstory are that (a) everyone has a history and (b) most of it isn’t very interesting,” Stephen King writes in “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft.”

“Stick to the parts that are, and don’t get carried away with the rest,” King says. “Life stories are best received in bars, and only then an hour or so before closing time, and if you are buying.”

When Ernest Hemingway talked about the fact that only one-eighth of an iceberg shows above the water, he was describing a theory of omission that represents a form of backstory. In his short story, “Hills Like White Elephants,” the backstory is that the couple sitting drinking wine as they wait for a train are discussing an abortion without ever saying the word. The original “Star Wars” movie and its first two sequels contain preconceived backstories that were later developed into prequels. Even its minor characters have backstories.

Other backstories are a form of foreshadowing. Early in the movie, “The Silence of the Lambs,” which hews closely to Thomas Harris’ novel, agent Starling, played by Jodi Foster, sees a lineup of the gruesome photos of serial killer Buffalo Bill’s victims.

“Thus, when Catherine, the senator’s daughter, is captured,” Morell notes, “we’re aware of the gruesome torments that await her. Further, because backstory reveals that Buffalo Bill keeps his victims alive for a certain number of days, the stakes are increased because time is running out for Catherine. When Starling confronts Bill in the climax of the novel, the backstory heightens the suspense.”

Backstories reveal characters motivations as these examples in “Backstory: The Importance of What Isn’t Told” by novelist K.M. Weiland demonstrate.

- The inability to measure up to his younger brother, which fuels Peter Wiggin’s anger and ambition (the “Ender’s Shadow” series by Orson Scott Card)

- The long-harbored guilt for brutal war crimes, which impels Benjamin Martin to avoid war (the movie “The Patriot”).

- The long years of loneliness which influenced John Barratt to accept the compulsory swapping of roles with his French lookalike (“The Scapegoat” by Daphne du Maurier).

As you compose your novel or screenplay and develop your characters, you have to know their backstory. Study the backstories in classic novels like Fyodor Dosteovsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” about Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, an impoverished law student who murders an elderly money lender. ShowTime’s “Dexter” uses flashbacks to reveal how a serial killer with a twisted ethical compass is born. Dickens launches “David Copperfield” with backstory. The backstory of the “Harry Potter” series is the murder of Harry’s parents by the dark wizard Lord Voldemort. Reread your favorite novels and study films to identify the back story, their purpose and the methods the writer used to develop and present them. to the reader

As you start work on your own story, it’s crucial to answer a ton of questions about your characters to make sure you understand who they are and where they came from. Here’s one of the most comprehensive that I’ve found. It’s long, but essential if you hope to write a story that raises the stakes for its characters, furnishes psychological realism and above all, make readers understand how and why your characters behave as they do. Backstory has many purposes in the creation of realistic characters. The most important is that it helps readers care about them.

Finding inspiration in reading: Tip of the week

Writing TipsFind inspiration in reading.

Writing teacher Donald M. Murray liked to say that when he read something that inspired him, “my hand itches for a pen.” “Writers,” he once wrote, “read to be inspired, to see the possibilities of language. They learn most about writing by writing, but they learn a great deal by reading.” If you’re having trouble finding inspiration or are stuck in place, choose a “sacred text.” It could be anything from Shakespeare’s plays or sonnets or the King James Bible to a novel or short story collection by one of your favorite authors. Read for pleasure. When something strikes you as wonderful, copy it out. See if you can apply its lessons to your own work. As I mentioned in the last issue, I’ve steeped myself in the “Collected Stories of John Cheever.” His diction has inspired me to work harder on my own word choices. His carefully woven sentences prod me to write with greater complexity. Reading writers whose work I admire helps me see what works in my own writing and what needs work. It can do the same for you.

Rituals to Write By

Craft Lessons

I’d heard the story many times, but I still couldn’t believe it.

Let’s face it, it sounded a little strange.

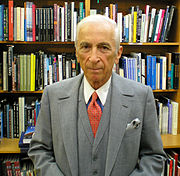

Gay Talese, the acclaimed narrative writer, a pioneer of New Journalism, pinned his manuscript pages to the wall of his office.

He then walked across the room to his desk. On it rested a pair of binoculars.

He picked them up and trained them on his pages to study them word by word.

Or so the story went.

Bizarre. Perhaps. But it seems to have worked.

Talese is the author of books and magazine articles that set the standard for narrative writing. One of them, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” famously demonstrated how you could write a profile without actually interviewing the subject.

Talese wouldn’t be the first writer to turn to a ritual, quasi-religious behavior.

Rita Dove, the former U. S. Poet Laureate, wrote by hand, standing up at a lectern with a candlestick on it. She wrote at the end of the day. She lit the candle and as the burning tallow began to flicker on the page, she began to compose.

When John Steinbeck was writing his classic novel ‘East of Eden,” he started each day by writing a letter to his editor Pascal “Pat” Covici.” By his side sat twelve round pencils sent spinning twice a day through an electric sharpener, each sharpened tip enough to last a page.

Gail Godwin, the novelist (“A Mother and Two Daughters,” Grief Cottage“) and essayist, lights two different kinds of incense. Godwin relies on other totems: crisp new legal pads and new No. 2 pencils with erasers that don’t leave red smears.

Rituals, if these acclaimed writers demonstrate, matter to writers. They are part of their process, almost religious-like gestures designed it seems to summon the Muse.

Allure of rituals

The rituals of successful writers hold a special allure for those trying to emulate their success.

Over the years, I’ve collected many examples. Unfortunately, many are unattributed. They may be apocryphal, their authenticity dubious.

But I’ve seen a picture of Rita Dove standing at her desk with the lighted candle glowing.

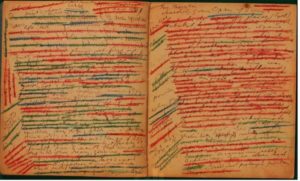

On the Internet, I found an image of a notebook page that James Joyce marked up with red crayons.

In her slim but rich and meticulously researched book, “Odd Type Writers:

From Joyce and Dickens to Wharton and Welty, the Obsessive Habits and Quirky Techniques of Great Authors,” Celia Blue Johnson does a remarkably thorough job documenting the rituals, working habits and environments of nearly 200 writers from Diane Ackerman to W.B. Yeats.

James Joyce wrote in bed wearing a long white coat and used crayons to mark up his notebooks (in the picture below, he chose red and green ) for “Ulysses.”

Truman Capote, author of the legendary “In Cold Blood,” insisted on leaving three–only three– cigarette butts in his ashtray. Honoré de Balzac, the 19th-century novelist, gulped dozens of cups of strong coffee every day–the exact amount is in question–to keep him going. The French writer Colette couldn’t pick up her pen before picking the fleas off her cat. Whatever works, I guess.

Some, like poet Robert Frost, could only write by night, Johnson recounts. As an aspiring fiction writer, J.D. Salinger huddled under his bedsheets at night, and “with the aid of a flashlight he began writing stories,” his editor William Maxwell recalled. William Faulkner wrote “As I Lay Dying” in just six weeks, churning out his novel during the night shift at the power plant where he worked.

Others, like Charles Dickens, Henry James, and Virginia Woolf trekked for miles in the countryside finding energy and inspiration along the way. Later in the modern age, the airplane became the favorite place of composition for “The Handmaid’s Tale” Margaret Atwood.

Environment matters to many writers. Marcel Proust famously lined the bedroom where he wrote with corkboard to keep out the noise and heavy curtains to blank light that might distract him from composing the classic, “Remembrance of Things Past.” Maya Angelou rented hotel rooms to write in. By her bed, “a bottle of sherry, a dictionary, “Roget’s Thesaurus, yellow pads, an ashtray and a Bible.”

“A room is far more than four walls. a ceiling, and a door. It’s a place where a writer can embrace, and even harness, her or his own idiosyncracies. In the solitude of a room, a writer’s creativity manifests not only on the page, but also in unique work habits.”

Celia Blue Johnson

I’ve been thumbing through Johnson’s book with great pleasure. It’s replete with fascinating examples demonstrating that “writers are a very quirky bunch,” sometimes bordering on the obsessive.

The Covid-19 Pandemic has altered the usual working spots for many writers, as author and teacher Matt Tullis found in this fascinating piece for Nieman Storyboard.

If you’d like to learn the rituals of some of your favorite writers, I recommend Johnson’s book, (I got a used copy off Amazon for under nine dollars. If you’d like to save some money, Maria Popova over at the inestimable Brain Pickings blog has already done a great service summarizing Johnson’s findings beyond the ones I’ve listed here.)

How writing rituals help

Tools matter. For the prolific French writer, Alexandre Dumas could only write poetry on yellow paper, pink for articles, blue for novels. Eudora Welty revised with scissors and pins–”straight pins, hat pins, corsage pins and needles-“-rather than paste. Langston Hughes wrote his letters in bright-green ink, Rudyard Kipling jet black.

To non-writers, these behaviors must smack of obsessive-compulsive disorder. To those of us struggling every day to create something worthwhile, they can be the difference between a productive day or one that ends in despair. Writers are fascinated by rituals, I believe, because they think if they mimic the routines of successful predecessors they might be able to achieve the same.

What may seem like ridiculous behavior to the non-writer, I recognize as actions with rational goals. They:

- Help writers get in the frame to write.

- Alleviate anxiety that prompts writer’s block, starting writing or procrastination, inability to get in the chair in the first place.

- Focus on the mundane as a way to set aside intrusions.

- Provide a routine to keep a writer on track

Of course, not everyone believes in rituals. Isaac Asimov, with over 500 published books to his name, dismissed the idea as “ridiculous.”

“My only ritual is to sit close enough to the typewriters so that the fingers touch the keys.”

I own a treasured paperback copy of Gay Talese’s first book, the 1961 collection, “Fame and Obscurity: A Book about New York, a Bridge and Celebrities on the Edge.” To call it dog-eared is a vast understatement; the cover hangs by a few threads. I carried it with me to a writing conference years ago where I knew my idol was speaking. During a break, I managed to get not only Talese’s autograph, but to confirm, from his own mouth, that he had indeed reviewed his manuscript pages with binoculars.

I was so awestruck that I neglected to ask an obvious question: why?

But if I had to guess, I think he would have answered, “Because it worked.”

May the writing go well,

Photograph by Filios Sazeides courtesy of unsplash.com

A choice, not a gift: Four Questions with John Woodrow Cox

Interviews

What’s been the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

So much about the way I approach stories has changed since the start of my career, but one lesson I learned early on has remained constant: Nothing matters more than the reporting. The most meaningful words in any story are the ones journalists earn before they ever sit down at a keyboard. I sometimes wish that wasn’t true, because capturing a revelatory detail or scene never gets easier. In a way, though, I also find comfort in that reality. I’m not the most naturally gifted writer I know, but the best reporting days are, more than anything, a product of hard work, and working hard is a choice, not a gift.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

My obsession with structure. It’s inconceivable to me today, but there was once a time when I didn’t outline anything before I wrote it, and I’m sure readers could tell. Now, I start thinking about a story’s potential architecture well before I’m done reporting it.

I just finished the draft of my first book, and it felt like I spent as many weeks working on structure as I did on writing. A blueprint of openings and endings — for the whole book, the chapters within it, the sections within them — migrated from dozens of notecards, spread out across the floor, to two massive sheets of paper taped to the wall in my home office. The journalist I was in college could never have imagined that scene.

What’s the best piece of writing advice anyone ever gave you?

Get out of the way. In other words: don’t overwrite; let your reporting do the work; cut the superfluous, whether that’s the unnecessary turn of phrase or the repetitive detail. I don’t know who first gave me that advice — or, rather, order — but I’ve heard some version of it from many great editors through the years. It’s always true.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer. what would it be?

I don’t use many metaphors in my writing and am reluctant to apply one to myself now, but I guess I could go with woodworker? A good woodworker, from what I gather, invests in his raw material. He fixates on small details and cares about precision. He plans before he builds. And, in my case, he works for a wise forewoman who knows just what to do when he saws the leg off of a chair.

John Woodrow Cox is an enterprise reporter at The Washington Post, currently working on “Children Under Fire,” a book being published by HarperCollins imprint Ecco. It will expand on his I series about kids and gun violence, a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in feature writing.

He has won Scripps Howard’s Ernie Pyle Award for Human Interest Storytelling, the Dart Award for Excellence in Coverage of Trauma, Columbia Journalism School’s Meyer “Mike” Berger Award for human-interest reporting, the Education Writers Association’s Hechinger Grand Prize for Distinguished Education Reporting and the National Association of Black Journalist’s single story feature award. He has also been named a finalist for the Michael Kelly Award, the Online News Association’s Investigative Data Journalism award and the Livingston Award for Young Journalists. In addition, his stories have been recognized by Mayborn’s Best American Newspaper Narrative Writing Contest and the Society for Features Journalism, among others.

John previously worked at the Tampa Bay Times and at the Valley News in New Hampshire. He attended the University of Florida, earning a bachelor of science in journalism and a master of science in management. He has taught narrative writing at UF’s College of Journalism and Communications and currently serves on the Department of Journalism’s Advisory Council.

Katherine Anne Porter on the ending

Writers Speak“If I didn’t know the ending of a story, I wouldn’t begin. I always write my last lines, my last paragraph, my last page first, and then I go back and work towards it. I know where I’m going. I know what my goal is. And how I get there is God’s grace.”

-Katherine Anne Porter

Libel Proof: Tip of the week

Writing TipsThe best defenses against libel are the truth and documents that support your story.

Bookbag: The value of not writing

Craft Lessons

I want to make a sacrilegious argument. If you want to be a better writer, don’t write. At least, not for a while.

How can that be? How can you improve if you’re not consistently practicing your craft, day in and day out?

If you’re like me, every day that passes without a word, a line, a paragraph written, seems like a day wasted. It brings to mind the French writer Simone de Beavuoir’s observation that I recently quoted: “A day in which I don’t write leaves a taste of ashes.” Not to mention that the motto at the end of my newsletters is “Never a day without a line.”

But there’s also something to be said, some writers argue, for letting the well of creativity fill up again after you’ve finished a story.

Whether you’re writing full time or on the side, as many do, fallow periods may be just what you need, these writers say. Journalists and freelancers dependent on constant output may not have this option, of course, but they can take mini-breaks if they intelligently manage their time.

There’s an agricultural analogy that supports the argument of not writing. For a while at least.

It’s not uncommon for farmers to plow their fields some seasons, but leave them unsown in order to restore their fertility.

The notion is reassuring because I’m suffering from an on-and-off spell of writer’s block. The days when I work productively on a fiction project are sadly outnumbered by those where I’ll do anything else. Incessant checking of my Twitter feed is a diverting substitute. Days have slipped by without my fingers touching the keyboard, except for producing my newsletters. The fog of self-doubt lifts some days, but even then my word count has amounted to just a few lines or scribbled phrases in my daybook.

As writers, we agonize over writer’s block, that occupational curse that holds our words at bay. But in “Maybe the Secret to Writing is Not Writing,” a provocative essay for Lit Hub I stumbled upon the other day, Kate Angus makes a persuasive case for taking a break.

“These days I’ve come to believe that it’s natural for many of us to go through periods when we put words to the page and times when we can’t. Maybe we can accept that we aren’t blocked at all,” she writes, “and that resting might just be part of our process.”

That’s what Roy Peter Clark, the influential writing teacher and my former colleague at The Poynter Institute, has been saying for decades. He turns the notion of procrastination on its head by urging writers to eschew negative self-talk when the writing machine spins to a halt.

“Turn your little quirks into something productive,” Clark says in “Writing Tools,” his best-selling guidebook. “Call it rehearsal or preparation or planning.”

It’s a potent solution, one that removes the stigma of writer’s block, replacing it with something positive.

Clark’s got a point. Your mind doesn’t shut off when you’re not writing. You’re still observing, an actor rehearsing a role, watching people and soaking up insights into the human condition — the subject matter of all great literature. Your mind still teems with story ideas, echoes with dialogue and creates possible characters. Like police officers, the writer is never really off-duty.

Angus quotes poet t’ai freedom ford (cq), who says there are “large swaths when I’m not actually writing, but I am doing lots of things to stimulate my muses and so I count it as writing. In that way, I don’t really believe in writer’s block, because when I consider the elements of my process, I’m most always writing (even if it’s only in my head).”

There are some who take the merits of not writing even further.

Poet Ada Limón feels ‘like there should be a permission slip for writers. Something you can sign for someone that says, ‘You don’t always have to write,’” she says in the essay. “You have permission to just be in the world and grieve and laugh and live and do your damn laundry. Writing comes when it comes, and it’s not the most important thing. You and all the little nuisances and nuances of life are what matter most. Don’t miss this gorgeous mess by always trying to make sense of it all.”

Taking a break isn’t without its risks. Ceasing regular writing may make it difficult to restart the habit.

Part of my problem is that I put aside my project while I finished a long short story besides my regular compendia of writing advice. I found it hard to regain my momentum, especially in the times of trouble we’re all living through. It’s hard not to be distracted and depressed by the steady drumbeat of tragic news, the pressures of pandemic and the gnawing uncertainty of life under quarantine even if, like me, you’ve been lucky enough to be spared personal loss. For those who haven’t please accept my deepest sympathies.

To deal with the fact that I’m writing less than I want or should, I’m reading more.

I’m savoring the acclaimed “Collected Short Stories of John Cheever,” 61 stories by the 20th-century master stylist called the “Chekhov of the suburbs.” Rarely does a page go by when I’m not copying out phrases, sentences or whole paragraphs to cherish, learn from and try to imitate. Reading generates writing. It amounts to a slow re-entry. I recommend it highly.

I may not generate hundreds of words at a stretch right now, but on walks with my dog, Leo, or by myself, I’ve been trying out scenes and staging imaginary plot points. They circulate in the back of my mind where I hope they will grow into something potent.

After reading Angus’s essay, I’ve been trying not to beat myself up if I deviate from my writing schedule, even though I still fear I’ll lose velocity and, heaven forfend, give up.

In the meantime, I’m learning to trust my subconscious. And I think it’s paying off. In recent days, I have found myself writing again, feeling excitement and energy rather than despair and inertia. The other morning I woke and couldn’t wait to start writing. I soon hit my daily word count and then nearly doubled it. And for the first time in a long time, I liked what I saw. Even a short break had topped off the tank of my creativity.

I think Angus and Limón make a valid point. Eventually, that farmer who lets his field go fallow for a season or more will plant again. With the soil replenished by time and the cattle and horses who graze upon it, the crop will be greater, richer. Who’s to say that won’t be the case if you set aside your writing, to soak in the “gorgeous mess” of life? You’ll have a wealth of material to draw on when you return to your desk and the chance for a harvest far greater than what came before.

The details write the story: Four Questions with Susan Ager

Interviews

Susan Ager is a prize-winning journalist of many years, now freelancing for National Geographic. Getting her start at the Associated Press, in Lansing, MI and San Franciso, for a quarter century she wrote and edited for the Detroit Free Press. She worked as a full-time coach, at the Free Press and dozens of other papers. For 16 years she wrote a thrice-weekly column and traveled the state of Michigan for a popular project she called “Tell Susan Ager Where to Go.” Her 1992 book “At Heart” is an anthology of her early work. She is a member of the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame, in part for pioneering coverage of the spread of HIV in her state. She lives in northern Michigan with her husband, Larry Coppard.

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

The details write the story, and the details only get better the more time you spend with your subject or topic. Even on daily stories, a second phone call never hurts. Repeat interviews with profile subjects provide exponentially more insight and info. (I have often been quoted as instructing writers I’m coaching, “Go to the bathroom,” which means take time off to think about what you’ve got and your next step – but you never know what you’ll learn from the shower curtain or the magnets on the mirror.) Immersion journalism is, of course, my favorite: Live with your person or live in the place. If you live by these principles, you will know so much that you can write your story from memory, without checking your notes, leaving XXXs where you’ve forgotten a small detail. This is tremendously freeing.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

That it gets both easier and harder. It becomes easier to craft sentences and paragraphs once you understand how readers consume words and ideas. It becomes harder to think through how a complex story should best be told. Which details to leave out is always challenging: You don’t want to over-spice your stew.

If you had to choose a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be and why?

A great writer – a status I occasionally achieve – seduces readers. Take a walk with me, even though you don’t know me. Hold my hand. Let me lead you down a path you’ve never walked before. You might feel wary, or tired, or feel the faint beginning of boredom, but take another step with me, and another. Haven’t I surprised you with almost every step so far? I’ll take care of you. I’ll make sure the path is easy or, if challenging, at least worth the effort. In the end, you’ll be glad you trusted me, and will want to spend more time with me again.

What’s the best piece of writing advice someone gave you?

“Write from memory,” mentioned above. And, “Just vomit.” Clean it up later. All that advice combined freed me from a bad habit of writing slowly, rewriting my first sentence three times, then rewriting the first paragraph endlessly — then flipping through my notebook and changing it all again. I tell writers now, “Get the clay on the table then shape it into the story you want.” Don’t check your notes until you’re done, then be cautious about including anything you had forgotten to include the first time. If it wasn’t important enough to remember, why add it now?