“A day in which I don’t write leaves a taste of ashes.

Author: chipswritinglessons_harnwk

Brief Daily Sessions: Tip of the week

UncategorizedWrte in brief daily sessions, no longer than 30 minutes each, for a total of two to three hours day to avoid burnout.

h/t Robert Boice

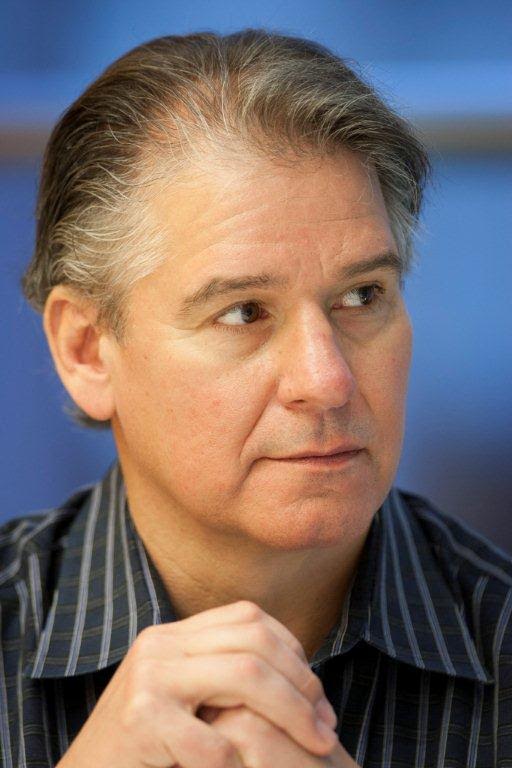

Doing the Work: Three Questions with Bryan Gruley

Interviews

What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

Do the work. That’s a variation on the familiar “ass in chair” exhortation, but it refers to much more than typing words on a screen. Mark Lett, my longtime boss at The Detroit News and later the executive editor of The State at Columbia, S.C., used the phrase often. “Do the work” means attending to all of the tasks—some more tedious than others—that lead to results. When I’m pursuing a non-fiction story in my day job as a feature writer for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine, doing the work means, for instance, looking at every page of notes, documents, and other materials I’ve gathered in my weeks of research, even though only about 1 percent of what’s there is likely to make it into my story. As a novelist, doing the work is more about sitting at my laptop every morning and putting words to digital paper. Whether it’s 300 or 500 or 1,000 words a day, if I keep doing the work, I know I’ll eventually have enough in front of me that I can begin to see my way to the middle of a book and, finally, an end. I’ve heard writers say, “That story just wrote itself.” If only.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

That people would profess to love something I wrote. I still get a thrill when a reader posts an online comment or sends me an email saying they liked one of my pieces or books. At the other end of the spectrum, I’m still disappointed when people dislike something I’ve written (which happens much more with fiction than non-fiction). My favorite comment ever is probably an email I received from one Evan Vetere, a Wall Street Journal subscriber. I had written a Page One story about a World War II lieutenant and the Jewish boy he rescued from Dachau. Mr. Vetere wrote me: “Your profession exists so people like you can write stories like this.” I’ll never forget it

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer what would it be?

Although it’s not entirely accurate, the one that pops immediately to mind is tortoise. I’m not a particularly slow writer, and sometimes, especially on deadline, I can be pretty fast. On September 11, 2001, I took 30,000 words of WSJ staff memos and turned them into a 3,000-word front-page story in under three hours. But I am tortoise-deliberate. I have a process that revolves mostly around elimination. In my non-fiction day job, I pile interviews, observations, documents and other stuff into big piles of clay that I then whittle away, getting ridding of stuff until what remains is my story. Fiction is different insofar as I have a lot more material I can use—virtually everything I’ve ever seen, heard, smelled, tasted, overheard, read, imagined, etc. I start by choosing what to put on the page. As the words multiply and the characters come more clearly into focus, the story actually begins to narrow because as I’m choosing where it will go, I’m also choosing where it will not, and the farther it goes in one direction, the less likely it’s going to go in infinite others. Then, when I’m rewriting, I’m doing a lot more subtraction than addition. Unlike some writers I know, I love rewriting, especially the tactile feel of using a pen to strike out words, phrases, and sentences. Eventually, I know that if I do the work and stick to my laborious process, I will give myself the best chance to produce something that someone will tell me they love.

Bryan Gruley is the award-winning, critically acclaimed author of “Bleak Harbor,” which Gillian Flynn called “an electric bolt of suspense,” and his latest crime thriller, “Purgatory Bay,” which Michael Connelly says is “impossible to put down.” Gruley was nominated for an Edgar for his debut novel, “Starvation Lake,” the first in a trilogy set in a fictional northern Michigan town. When he’s not making things up, Gruley writes long-form features on a wide variety of topics as a staff writer for Bloomberg Businessweek magazine. He has won numerous prizes for his journalism, and shared in The Wall Street Journal’s Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the September 11 terrorist attacks. He lives in Chicago with his wife, Pam.

CRAFT LESSON: Attitude is all

Uncategorized

When I think of the hundreds of writers I have coached over the years, the best ones impressed me with their intellect and creativity. But what stands out most are not these strengths, important as they may be. Instead, it’s their attitude that makes them special in my eyes.

“The attitude we choose is by far the most important choice we make every day.”

LOU HOLTZ

Three decades of working with writers have convinced me that attitude — a way of thinking that is reflected in a person’s behavior — matters more than talent.

Talent may open the door, but attitude gets you inside the room.

“Most people place an undue emphasis on talent. I don’t doubt that it exists, but talent is essentially a potential for something. The issue is really not talent as an independent element, but talent in relationship to will, desire and persistence. Talent without these things vanishes and even modest talent with those characteristics grows.”

MILTON GLASER

Writing is a craft. It relies on a set of skills: reporting and researching, writing and revision (and more revision), understanding of structure, and facility with language, syntax, and style. Mastery requires years of study, work and above all, patience. Malcolm Gladwell famously estimated that achieving mastery in many fields requires 10,000 hours of work. True or not, there’s no doubt that becoming a good writer takes an enormous expenditure of time and effort. And without the right attitude, the willingness to do that work, the chances of success are slim to none.

In a field where so much — success and rejection, for starters — is out of a writer’s hands, attitude is one thing we can control. We can decide whether to procrastinate or write every day, give up or commit to one more revision, try our hand at a different genre, or learn and learn from other writers rather than be consumed by jealousy about their achievements.

Inspired by the wisdom of acclaimed designer Milton Glaser, legendary coach Lou Holtz and David Maraniss, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author, I found myself musing about the nature of attitude and its importance to writers seeking success, including myself. Here’s what I came up with. It’s a partial list; I hope you’ll add to it in the comment section.

- Attitude matters than more than, talent.

- Attitude makes the difference between giving up and sticking with a story.

- Attitude means making one more phone call, writing one more draft, burrowing into your draft one more time to refine and polish your story.

- Attitude means a collaborative relationship with editors rather than a toxic one.

- Attitude means submitting a story the same day someone rejects it.

- In the end, attitude is what makes the difference between failure and spectacular success

CRAFT QUERY: What does attitude mean to you?

May the writing go well.

Photograph by Jeff Sheldon courtesy of unsplash.com

Attitude is all

Craft LessonsWhen I think of the hundreds of writers I have coached over the years, the best ones impressed me with their intellect and creativity. But what stands out most are not these strengths, important as they may be. Instead, it’s their attitude that makes them special in my eyes.

Three decades of working with writers and editors have convinced me that attitude—a way of thinking that is reflected in a person’s behavior matters more than talent.

“Most people place an undue emphasis on talent,” influential designer Milton Glaser said. “I don’t doubt that it exists, but talent is essentially a potential for something. The issue is really not talent as an independent element, but talent in relationship to will, desire and persistence. Talent without these things vanishes and even modest talent with those characteristics grows.”

Talent may open the door, but attitude gets you inside the room. And as legendary coach Lou Holtz said, “The attitude we choose is by far the most important one we make every day.”

A good attitude can pay off. That was the case for David Maraniss when he was writing investigations and series at The Washington Post. When news broke, he was one of the first to pitch in. “Even if I’m doing a series,” he once told me, “I say, ‘Look, if you guys need me, I’d be happy to do something.’ I try to be in a position to say yes, and I try to volunteer so that I can have enormous freedom the rest of the time.

“I find that so many reporters keep banging away at their editors and having frustrating confrontations about what they have to do or don’t have to do. I’ve always found it much more effective to do what I want to do by doing some things for them.

“I like newspapers, and I love to write on deadline. And so I volunteer. But one of the reasons I do that is so that there’s a fair exchange, where they know that I’m always around when they need me, and then in return, I get a lot of freedom the rest of the time to do what I want to do.” Maraniss has gone on to write a string of best-selling critically acclaimed books.

Writing is a craft. It relies on a set of skills: the ability to generate ideas, excellence in reporting and researching, writing and revision (and more revision), understanding structure, and facility with language, syntax and style. Mastery requires years of study, work and, above all, patience. Malcolm Gladwell famously estimated that achieving mastery in many fields requires 10,000 hours of work. True or not, there’s no doubt that becoming a good writer takes an enormous expenditure of time and effort. Without the right attitude and the willingness to do that work, the chances of success are slim to none.

In a field where so much — success and rejection for starters — is out of the writer’s hands, attitude is the one thing that we can control. We can decide whether to procrastinate or write every day no matter how uninspired we feel, give up or commit to one more revision, try our hand at a different genre, or learn from other writers rather than be consumed with jealousy about their achievements.

Inspired by the wisdom of Maraniss, coach Holtz and designer Glaser, I found myself musing about the nature of attitude and its importance to writers, including myself, who seek success. It’s a list I printed out and keep close as I work. I hope it may be of value to you.

- Attitude matters more than talent.

- Attitude makes the difference between giving up or sticking with a story.

- Attitude means making one more phone call, writing one more draft and burrowing into that draft one more time to refine and polish your story.

- Attitude means a collaborative relationship with editors rather than a toxic one.

- Attitude sometimes means submerging your own interests to contribute to the greater good.

- Attitude means submitting a story again the same day someone rejects it.

- In the end, attitude is what makes the difference between failure and spectacular success.

Nicholson Baker on writing every day

Writers Speak“If you write every day, you’re going to write a lot of things that aren’t terribly good, but you’re going to have given things a chance to have their moments of sprouting.”

Endgame: Tip of the week

Writing TipsFinish the story you started, no matter how much you hate it. You can’t revise what isn’t written.

Making peace with your weaknesses: Four questions with David Finkel

Interviews

David Finkel. Photo by Lucian Perkins

What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

If reporting is always getting the name of the dog, writing is knowing when not to use the name of the dog.

What has been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

The surprise is that I could even have a writing life, but that’s a lame answer, so let me go back to the first question. Another lesson I’ve learned is the importance of being methodical. Not that there’s one, perfect method, but the one that has worked for me is knowing my ending before I begin writing. I used to get so lost in writing when I didn’t do this, as if magic, rather than method, would solve the day. Now, if I know my ending, and I mean the actual ending, down to the last sentence, even the last word, it means I know that my reporting is finished and I have a story to tell as opposed to, say, a caption to write. It also means I know the emotional tone of the piece and I can structure my material to get there as consistently and efficiently as possible. In every story I’ve done over the second half of my career, including my books, I’ve known my ending before I wrote the beginning.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be?

I’m terrible at metaphors, so I’m going to pass on this one except to say part of writing is making peace with your weaknesses and avoiding them.

What’s the best piece of writing advice anyone ever gave you?

The first came from a writer who is better than me, and who I was trying to impress by describing a story structure I had worked out that was so sophisticated I was sure it was going to dazzle her. In the kindest way, she said: You know, I’ve found in my own work that the more complicated the structure is, the more time I have to spend getting myself out of corners, and the simpler it is, the more room I have to write my story.

And the second is that old Hemingway advice: As a writer, you should not judge. You should understand.

David Finkel is a journalist and author of “The Good Soldiers,” an account of a U.S. infantry battalion during the Iraq War, and “Thank You For Your Service,” a sequel that chronicles the challenges faced by soldiers and their families in war’s aftermath. An editor and writer for The Washington Post, Finkel has reported from Africa, Asia, Central America, Europe, and across the United States, and has covered wars in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Among his honors are a Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting in 2006 and a MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant” in 2012. He lives in the Washington, D.C. area.

Craft Lesson: Mornings are made for writing

Craft Lessons

When do you write? First thing in the day or last?

It depends on the writer, of course.

But many highly successful writers, whether by habit or belief, seem to find mornings to be the most productive time. Neuroscience backs them up.

An admittedly unscientific search culled through interviews with working writers, quote collections and an excellent book, “Daily Rituals: How Artists Work,” by Mason Currey, revealed repeated examples of writers choosing break of day.

“Get up very early and get going at once,” was the preference of poet W.H. Auden. “In fact, work first and wash afterwards.” Mornings were the rule for Nobel laureate Saul Bellow who would write for 3 to 4 hours at a sitting.

When Ernest Hemingway was working on a story, he said, “I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write.

Pre-dawn is the preference for Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami. When I’m in writing mode for a novel,” he says, “I get up at 4:00 am and work for five to six hours.

Not every writer has the freedom or the inclination for morning writing. Exiled to military school at 15, J.D. Salinger wrote his early stories at night under his blanket by flashlight. “There’s a mislaid family of readers and writers at night,” Matt Shoard wrote in a survey of nocturnal writers. And nighttime writers are a passionate, if somewhat cranky lot. Maybe it’s the caffeine.

“Is it the peace and quiet? asked Stephanie Meyer who wrote “Twilight” mostly at night. Nighttime composition is also the preference of Danielle Steele, Jacquelyn Mitchard and Barack Obama. Allison Leotta used to write her legal crime thrillers before work as federal prosecutor. But that changed to nights after she became a mother.”Now,” says Leotta, “the sound of a softly snoring baby triggers a Pavlovian response in me to start typing.”

For every nighttime writer, though, there seem to be many more who prefer early morning, close to dream sleep when the unconscious still lurks.

Brain science suggests that a morning writing schedule is geared to creativity. Moderate levels of the stress hormone cortisol aid focus. It also helps that willpower is strongest at the start before the day’s stresses sap it. The writer can rely on the prefrontal cortex, which governs planning, decision-making, problem-solving, self-control, and acting with long-term goals in mind.

The routines of successful writers suggest that they’ve discovered, without a degree in neuroscience, the power of the morning writing session.

Children’s novelist Lloyd Alexander woke at 4 a.m. to write because, he said, “you are closer to the roots of the imagination. At the end of the day the edge is off—You’re not the same person as you were in the morning. “

Barbara Kingsolver described a routine that starts before dawn. “Four o’clock is standard. My morning begins with trying not to get up before the sun rises. But when I do, it’s because my head is too full of words, and I just need to get to my desk and start dumping them into a file. I always wake with sentences pouring into my head. So getting to my desk every day feels like a long emergency.”

“Four o’clock is standard. My morning begins with trying not to get up before the sun rises. But when I do, it’s because my head is too full of words, and I just need to get to my desk and start dumping them into a file. I always wake with sentences pouring into my head. So getting to my desk every day feels like a long emergency.”

Barbara Kingsolver

Of course, some writers have no choice. Work or family demands may make it impossible to start work first thing. You may have to steal time; drafting at your desk over a quick lunch, after dinner, when the kids are in bed. Crime writer Leotta also writes when her baby is napping. I know writers who work late at night after the house is quiet. They may sacrifice sleep but meet their daily quota.

I’ve tried both times of the day, and while I sometimes find afternoons are productive, in the end I’ve come to prefer the early morning quiet before the day’s responsibilities intrude. Otherwise, as the day goes by my willpower and energy wilt. I keep in mind the words of Goethe, the German master: “Use the day before the day. Early morning hours have gold in their mouth.”

Daytime writers like Italo Calvino, the Italian journalist and fiction writer, feared the effects of nighttime writing which keep their mind moving when they preferred it would rest. “I’m terrified of writing at night,” he told an interviewer for The New York Times, “for then I can’t go to sleep. So I start slowly, slowly writing in the morning and then go on into the late afternoon. “

You may want to experiment, toggling between day and night to discover your best writing time. But if you choose AM over PM, here are suggestions to get you moving and writing.

- Wake up. Get up. If you’re’ the type who tends to overlseep, don’t hit the snooze alarm. Brew your coffee or tea, take it to your desk.

- Quarantine yourself. Susan Sontag vowed in her diary to tell people not to call her in the morning and she resolved not to answer the phone. Lock your office door. David Margolick uses Flents Quiet Please foam earplugs to buffer the din outside his Manhattan apartment while he’s working on his books about comedian Sid Caesar and scientist Jonas Salk.

- Start off easy. If you begin first thing trying to write a masterpiece, writer’s block will likely ensue. Begin writing in your journal, making notes for the day. Read “sacred texts.” from the Bible to your favorite novel or poem, writings that inspire you to start your own compositions as the sun comes up.

May the writing go well.

Photography by Nick Morrison courtesy of unsplash.com

Peter De Vries on bacon in a skillet

Writers Speak“When I see a paragraph shrinking under my eyes like a strip of bacon in a skillet, I know I’m on the right track.”