Before writing, put away your notes. The story’s in your head and heart.

h/t Lane DeGregory

Before writing, put away your notes. The story’s in your head and heart.

h/t Lane DeGregory

“The muse has to know where to find you.”

Writing may start in your head, but it has to come out of there, onto the page or the screen.

For that to happen, you have to sit down with a pen and notebook or in front of a computer.

Not everyone recognizes that.

Jericho Brown, a poet and head of the creative writing program at Emory University, posed this question to a class the other day: if you show up for other people—for dentist appointments, making sure kids get to school on time, etc.—why can’t you show up for yourself, to write?

Some might say laziness, but that’s a facile explanation. More likely, it’s resistance, the fear that there’s no point. I have no ideas, you think. I don’t know how to keep going. I’m just no good.

They’re understandable worries, but you have to fight them.

Whatever the reasons, you have to turn up. That’s the only way you can come close to achieving your dreams. It takes discipline, as even the most successful writers have learned.

“I have to walk into my writing room and pick up my pen every weekday morning,” says Anne Tyler, whose discipline has produced 22 novels. “If I waited till I felt like writing, I’d never write at all.”

Tyler doesn’t wait for a muse, that mythical source of inspiration for the creative artist. Like other successful and productive writers, she turns up.

“I go to the office every day and I work. inspiration itself is not something I have any control over.”

Nick Cave

“I go to the office everyday and I work,” says musician Nick Cave. “Inspiration itself is not something I have any control over.”

Depending on the needs of your family and your work life — if writing is, as it is for most, a second job — you may not be able to write every day. Sometimes a few days or a week may go by, although the longer between sessions, the greater the chance of losing momentum.

To turn up regularly, you’ll need to find—or steal—writing time when you can. An example from my writing life can show you one way.

When I had a job that demanded 10-12 hours a day and a family with a toddler and twin infants, the only time I could write was first thing in the morning when the house was asleep.

I would brew a cup of strong tea and make my way downstairs, careful to avoid squeaks that might awake my sleeping family, to the basement where, crammed into a corner, I had installed a desk and chair.

I usually had less than an hour before I had to get ready for work. I would make notes, draft passages and revise on my desktop and hit save.

I then took a Metro subway to the National Press Building in Washington DC, where I worked as a newspaper reporter. The ride was just 30 minutes long, but I decided to take advantage of that time as well.

I had been inspired to do so after reading that Scott Turow finished his best-selling crime thriller, “Presumed Innocent,” on his commute to Chicago where he worked as an assistant U.S. attorney.

“I wrote 26 to 28 minutes a day,” he told an interviewer after his success. “It doesn’t sound like a lot, maybe, but if I hadn’t done it, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

“I wrote 26 or 28 minutes a day. It doesn’t sound like a lot, maybe, but if I hadn’t done it, we wouldn’t be having this conversation.”

Scott Turow

At the time, I had been working, without much success, in my pre-dawn basement sessions, on a short story about a sports-challenged mother thrust into the role of coach one Saturday at her daughter’s Little League game.

I don’t have a clue where the idea came from, except for the fact that I am sports-challenged with a boyhood history of humiliating days on the baseball field.

But drawing on those experiences, and armed with a legal pad, I found myself drafting with ease as the subway made its subterranean way to my day job. Perhaps because it seemed less permanent than words flickering on my computer screen.

There were mornings when I had to use my commute to keep up with work, but I managed to finish a complete draft in a few weeks. I then spent a few more weeks revising it, marking up a printout I carried in my briefcase. Turning up to write was paying off.

After I finished the story, I sent it to magazines.

Soon, I had a tidy pile of rejection slips. I assumed I had exhausted all the possibilities.

Then a friend, Rick Wllber, who writes sports fiction, among other genres, told me about Elysian Fields Quarterly: A Baseball Review.

Long story short: they published “Calling the Shots.”

“I have to walk into my writing room and pick up my pen every weekday morning. If I waited till I felt like writing, I’d never write at all.”

Anne Tyler

The experience taught me a vital lesson about my craft that I hope you’ll take to heart. It doesn’t matter whenever, wherever, or for how long you write. At dawn. On your lunch break. Before bed. On a park bench. In a coffee shop or your home office. Or the subway.

You don’t have to write for very long. But you must stick with it. Try not to miss a day, or you’ll lose momentum. Very soon you’ll have a draft you can revise and that book chapter, essay or story will be that much closer to completion.

What’s most important is that you never stop turning up to write. As often as possible. That way “the muse” knows where to find you.

CRAFT QUERY: How do you make sure you turn up to write?

May the writing go well.

I saw that Dan Barry said that a big lesson for him was that the process gets harder. That feels true. But for me the process has gotten easier. I am not Sisyphus kicking that stone downhill. But I feel that I am at least rolling it on a level plain. But it only gets easier if you are willing to relearn the big lessons with each project. I’m talking about books now. I’ve written six in twelve years. I have a process that I borrowed from Bill Howarth’s description of John McPhee. I need my raw material, my index cards, my file folders, my bulletin board. If I try a shortcut, if I lean too heavily on my experience, if I try to dance over a step, I usually crash to the bottom of the staircase. Use the process. Follow the steps. Trust the process. You have to trust. Even if it’s not going well at this moment, keep at it. Realize that the imperfection you feel right now is necessary. There was a great bowler from Texas named Billy Welu who used to be a color commentator for televised bowling tournaments. He would point out that some bowlers with big hooks needed to roll the ball at the edge of the gutter in order for it to curve into the pocket for a strike. “Trust is a must,” he would say in a Texas drawl, “or your game is a bust.”

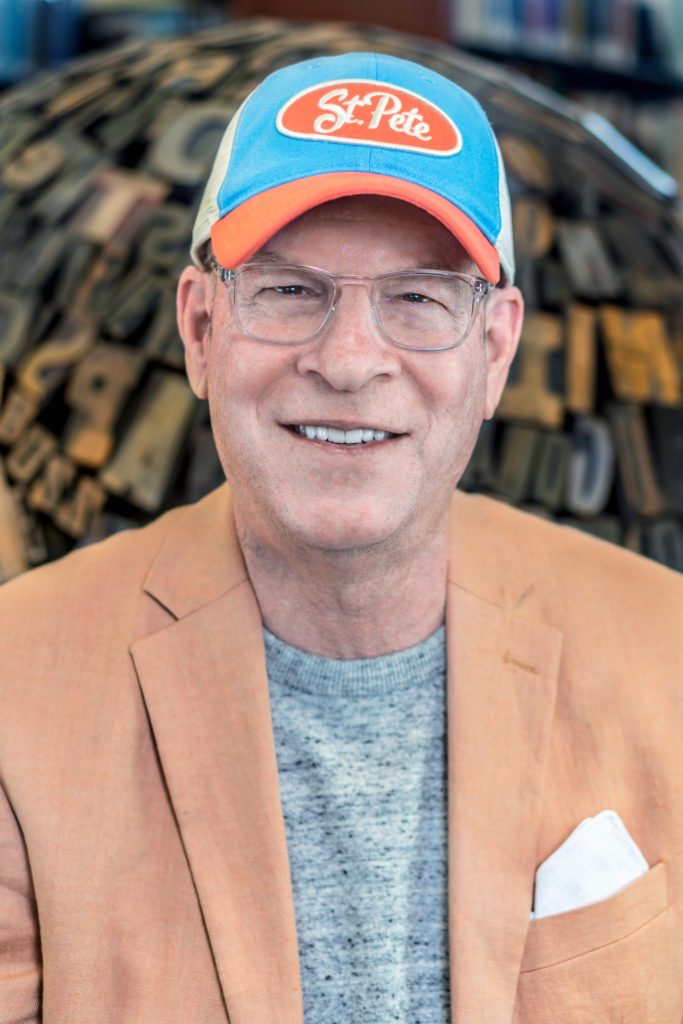

My biggest surprise as a writer came when I was about 30 years old. It surprised me again when I was about 60 years old. This had to do with my personal and professional identity. That is, how I identified myself. I meet people all the time who say, “I’m not a writer, but I am working on a novel.” Or “I write reports at work all day, but I’m not saying I’m a writer.” I play rock and roll piano. And on occasion I hit a golf ball. I am not Jimi Hendrix or Tiger Woods, but I feel comfortable calling myself a musician and a golfer. I was trained in graduate school to become a young English professor. And I wrote a Ph.D. dissertation about Chaucer, but I did not consider myself a writer. I became a newspaper writing coach, but did not call myself a writer. In 1979 I had about 250 bylines in the St. Petersburg Times. Finally, it hit me: “You know, Roy, maybe you could be a writer.” It feels crazy in retrospect: becoming a writing coach BEFORE I embraced the identity as a writer. Thirty years later, I could easily say I was a writer and a teacher of writing. Then it happened again. I wrote the book “Writing Tools” – followed by five more with Little, Brown. LB published Emily Dickinson! “Holy shit,” I thought, “I’m not just a writer – I’m an author!” If you write, you’re a writer. If you auth, you’re an author.

I am fascinated by the work of Phoukhoun Phimsthasak, a woman who made her way from Laos to America. She has an amazing personal story of escape, rescue, renewal, and hard, hard work. My wife and I know her as Jane. She does manicures and pedicures. As I metaphor, I can think of myself as a nail specialist. I work with an elaborate tool set, and a process that has a set of predictable steps, with some special challenges and surprises along the way. My mission relates to both utility and beauty, but also to listening and public service. It’s also about relationship building and referral, because there are a lot of nail specialists out there and many of them are good. But I want you to keep coming back to me.

Roy Peter Clark is senior scholar at the Poynter Institute. He has taught writing at every level — to schoolchildren and Pulitzer Prize- winning authors — for more than forty years. A writer who teaches and a teacher who writes, he has written or edited 19 books, including “Writing Tools”, “The Glamour of Grammar, “”Help! for Writers,” “How to Write Short,” and “The Art of X-Ray Reading.” His latest — a writing book about writing books — is due out in January: “Murder Your Darlings: And Other Gentle Writing Advice from Aristotle to Zinsser.” He lives in St. Petersburg, Florida, hits a golf ball now and then, and plays keyboard in a blues band .

“One’s ability to rewrite is the key to becoming a writer, far more important than native talent or inspired writing sessions.”

“If you talk to someone long enough, you find common points. These things comes out, and you ask for them. If I ask too early, they won’t come through But if we talk long enough and they feel they can trust me, then they hand over things.”

Quotes have to earn their way into a story. They should occupy a place of honor. Rule of thumb: if it takes more than one breath to read a quote out loud, it’s too long.

h/t Lex Alexander/Kevin Maney

Listen. Sounds basic but in the hustle to get out the news, sometimes it gets lost. It’s OK and even a good habit to allow long pauses in an interview. Quiet moments give the subject a chance to reflect. It’s hard to stifle the impulse to fill that space with a follow-up, clarification or comment, but sometimes that moment produces a deeper response. I learned this essential lesson while working with my colleague, Dave Killen, a film editor, on a documentary series. He needed people’s answers to trail off naturally. As the interviewer, that meant less give-and-take in favor of a more intentional effort to allow more space between questions. Some of the richest responses emerged from those pauses.

It’s humbling to be trusted with someone’s story, especially if it involves sexual assault. I’ve written a lot about victims of sex crimes and other crime victims still coping with deep trauma and an unsatisfying criminal justice system. Their faith in institutions and in people is often shaken or even shattered. Trusting me, a journalist and stranger, with their accounts is a big leap of faith and a reminder of the critical role we play as truth-tellers.

I’d say my career has been a dark mirror of sorts. I’ve spent most of my 26-year career reporting on crime and justice. I’ve written about white supremacists, bad cops, predators and serial killers. The dark side of human nature — greed, rage and power — intrigues me. I chalk that up to growing up in Rhode Island in the 1970s and 1980s where public corruption and organized crime were always page one news.

Noelle Crombie is an enterprise reporter at The Oregonian. She has reported extensively on crime and justice. She reported and wrote “Ghosts of Highway 20,” a 7,000 word narrative and 5-part documentary series focused on the victims of serial killer who targeted vulnerable women along U.S. 20 in Oregon. From 2012 through 2016, she led The Oregonian‘s groundbreaking cannabis coverage, which focused on government accountability. Before coming to The Oregonian in 1999, she was a reporter for The Day in New London, Connecticut. She grew up in Rhode Island and received a bachelor’s degree in government from Smith College.

Craft Query: How would you answer these questions?

May the writing go well.

Photograph by Beth Nakamura/

Using a tape recorder has taught me my most important lesson of interviewing: to shut up. It was a painful learning experience, having to listen to myself stepping on people’s words, cutting them off just as they were getting enthusiastic or appeared about to make a revealing statement.

There were far too many times I heard myself asking overly long and leading questions, instead of simply saying, “Why?” or “How did it happen?” or “When did all this begin?” or “What do you mean?” and then closing my mouth and letting people answer.

It took a long time but eventually, I learned an important lesson: people hate silence. It makes them uncomfortable. And when they’re being interviewed, they’re especially sensitive to a reporter’s behavior. They’ll answer your question and then wait for the interruption that almost always follows. If you don’t butt in, they will keep talking.

There’s a great scene in the 1976 movie, “All the President’s Men,” when Robert Redford, as Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward, is asking a Republican businessman how his $25,000 check ended up in the Watergate money trail. It’s a dangerous question, and the source is skittish. “I know I shouldn’t be telling you this, he says.

Woodward remains silent; you can almost see him praying, “Tell me, please.” But he restrains himself and, suddenly, the man blurts out a damaging truth and then can’t stop. Before long, he’s implicated a top Nixon campaign official in the coverup. The moral here: To get people to talk, we need to learn the power of silence and master the art of listening.

Effective writers know they need to get their sources to reveal themselves, to provide the information they need for their stories, and, most important, to offer the human voices that bring a narrative to life.

“Silence opens the door to hearing dialogue, rare and valuable in breaking stories,” says Brady Dennis, of The Washington Post.

James B. Stewart in “Follow the Story: How to Write Successful Nonfiction” draws a distinction between “contemporary quotes — the journalism staple, spoken in answer to a reporter’s question — and “narrative quotes,“ uttered as dialogue or snatches of a character’s speech.

Contemporary quotes have their place. In many cases, the only way reporters can get a quote from President Donald Trump is to ask a question and capture his shouted response over the din of whirring helicopters of Air Force One.

Narrative quotes are much more revealing and require a reporter’s listening ear that is capable of snatching the butterfly of dialogue as it floats through the air. Good stories combine the two types.

In a story about a two-car collision that killed two Alabama sisters traveling to visit each other, Jeffrey Gettleman of The New York Times used simple quotes that illustrated what the Roman orator Cicero called brevity’s “great charm of eloquence.”

“They weren’t fancy women,” said their sister Billie Walker. “They loved good conversation. And sugar biscuits.”

Just 11 words, in quotes, yet they speak volumes about the victims. That’s a powerful contemporary quote, but Gettleman also listens for narrative ones, too.

As the service closed, relatives walked slowly back to their pickups. Gettleman captures a four-word narrative quote that reflects the region’s dialect and the minister’s concern for his flock.

”Y’all be careful now,” the pastor said.

“Learning to listen has been the great lesson of my life,” David Ritz wrote in The Writer.“

“You can’t capture a subject or render someone lifelike, you can’t create a living voice, with all its unique twists and turns, without listening. Now there are those who listen while waiting breathlessly to break in. For years, that was me.”

Ritz learned to embrace the idea of “patient listening, deep-down listening, listening with the heart as well as the head, listening in a way that lets the person know you care, that you want to hear what she has to say, that you’re enjoying the sound of her voice.”

That’s what an effective interviewer learns to do.

For decades, historian Robert A. Caro has been convincing people who knew and worked with the notoriously private President Lyndon B. Johnson to open up. His secret: silence.

“In interviews, silence is the weapon, silence and people’s need to fill it,” Caro writes in “Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing,” his illuminating book about the reporting methods behind his magisterial biographies of LBJ.

Caro employs a strategy other interviewers would be wise to adopt.

“When I’m waiting for the person I’m interviewing to break a silence by giving me a piece of information I want, I write “SU” (for Shut Up!) in my notebook. If anyone were ever to look through my notebooks, he would find a lot of “SU”s.”

During your next interview, ask your question. Then:

You’ll be amazed at the riches that follow.

May the interviewing go well.

Comment question: How do you get your sources to open up?

Photo by Ocean Biggshott on Unsplash

Adapted from “News Writing and Reporting: The Complete Guide for Today’s Journalist,” by Chip Scanlan and Richard Craig.

“The best work that anybody ever writes is the work that is on the verge of embarrassing him, always. It’s inevitable.

Eminent historian Robert A. Caro has been at work on his acclaimed multi-part biography of President Lyndon B. Johnson for decades. Now in his early 80s, he’s working on number five.

“Today everybody believes fast is good. Sometimes slow is good.”

ROBERT A. CARO

Caro is a former investigative reporter who long ago learned the power of “turning over every page” in the archives he haunts.

He describes his methodology in a new book, “Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing.” but if you want a Cliff Notes version, Popular Mechanics has published a fascinating interview with him.

It’s a surprising venue, until you realize the publication is fascinated by his electric typewriter. It’s a Smith Corona Electra 210.

Caro wrote his first book, “The Power Broker” on one. He likes them so much he bought seventeen of them when the manufacturer ceased production of the model decades ago. Nowadays, some people keep them around mostly to address envelopes and for short notes.

I’ve read lots of interviews with Caro; this conversation, which focuses on the value of analog vs. digital in his research and word processing, is one of the more interesting.

Top quote: “Today everybody believes fast is good. Sometimes slow is good.”