Growing up, I thought writers were magicians and I was screwed because I knew I wasn’t.

Writing a news story as a cub reporter felt like hacking my way through a jungle. Panicked, sweaty, I flipped through my notes and flailed away at the keyboard, desperate to make deadline and convinced I wouldn’t. I kept my editors waiting, which frustrated them, but they got my copy eventually, flawed though it was, and it made it into the paper. It was a painful process without any clear direction behind it.

As the years passed, not much changed, until one day in 1981 when Donald M. Murray was hired as the writing coach at The Providence Journal-Bulletin, where I had gotten a job after journalism school.

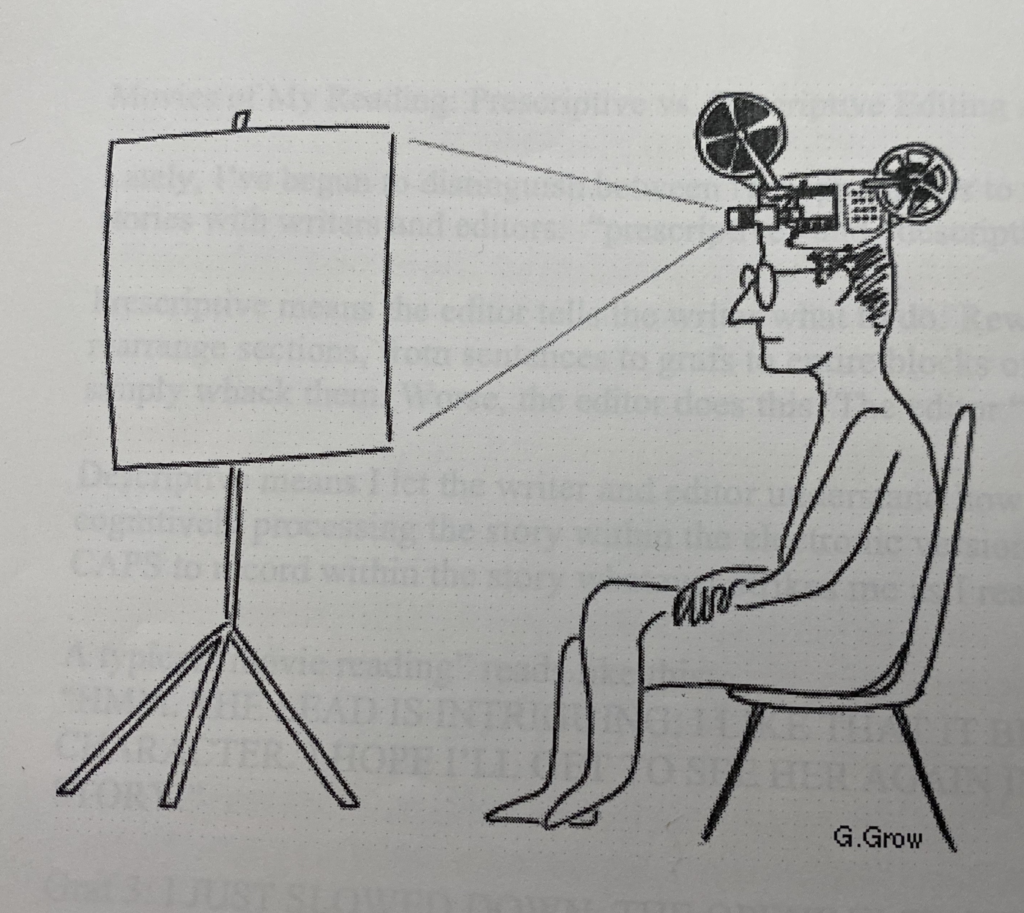

“Writing may be magical,” he told us at the first workshop, “but it’s not magic.”

I sat up straight and started scribbling in my notebook as he went on. “It’s a process, a rational series of decisions you make and steps you take, whatever the assignment, length or deadline,” said Murray, a Pulitzer Prize winner who taught journalism at the University of New Hampshire.

That lesson was the most important element of my education as a writer. I didn’t have to be a magician after all.

By following the steps that produce effective writing, you can diagnose and solve your writing problems. Reporters and editors who share a common view and vocabulary become collaborators rather than adversaries.

THE WRITING PROCESS: STEP BY STEP

1. IDEA

Good journalists get assignments or come up with their own ideas. Editors expect enterprise and rely on reporters to see stories that others don’t.

Tip

Look for ideas in your newspaper and others. Look online, in social media and in discussion boards. Ask yourself, what would I want to read about? Ask people you meet what’s missing in your paper, in your broadcast or on your website.

2. REPORT

Collect specific, accurate information. Not just who, what, when, where, and why, but how. What did it look like? What sounds echoed? What scents lingered in the air? Don’t be stingy with your reporting.

Tip

Look for revealing details. “In a good story,” says David Finkel of The Washington Post, “a paranoid schizophrenic doesn’t just hear imaginary voices, he hears them say, ‘Go kill a policeman.” Use the five senses in your reporting and a few other ingredients: place, people, time, drama.

3. FOCUS

Confronted with a wealth of reporting, journalists can get lost in the weeds, as I did. Good stories contain a theme—best expressed in one word, like loss or corruption—that leaves a single, dominant impression. Everything in the story must support it.

Tip

What’s the news? What’s the point? What does my story say about life, about the world, about the times we live in? What is it really about— in a single word? Your answers point you forward, frame your story and tell your audience why it matters.

4. ORGANIZE

Generals wouldn’t go into battle without a plan. Builders wouldn’t lay a foundation without a blueprint in hand. Yet organizing information into coherent, appropriate structures is an overlooked activity for all too many journalists.

Tip

Make a list of the top five elements you want to include. Number them in order of importance. Structure your story accordingly. Or, organize to build dramatic tension. Identify the beginning, an introduction of a problem or challenge. Then establish the middle, where conflict increases. Finally, establish the ending, a climax and resolution to the conflict.

5. DRAFT

Discover by writing, learning what you know and need to know. Freewrite your first draft without your notes. Go back and fill in the blanks.

Tip

Pulitzer Prize winner Lane DeGregory stashes her notes in her car before writing. “The story isn’t in your notebooks,” she says. “It’s in your head. And heart.“

6. REVISE

Circle back to re-report, re-focus and reorganize. Good writers are never content. Find better details, a sharper focus, a beginning that captivates and an ending that leaves a lasting impression.

Role-play the reader. Does the lead make you want to keep reading? Does it take too long to learn what the story is about and why it’s important? What questions do you have about the story? Are they answered in the order you would logically ask them? Make a printout. Cut, move, add. Make the changes on your computer.

Trust the process. The magic will happen.