When I hear the word “revision,” I think:

- I failed. I should have gotten it right the first time.

- I have no clue how to revise my story.

- I don’t have time to revise.

- Yippee! I’ve got another chance to make my story shine.

Too many writers would pick 1, 2 or 3 from that list. Many writers equate revision with failure. “If I were more talented,” they think.” I wouldn’t need to revise.”

“My editor’s a sadistic hack” they complain when a story has been sent back for revising. “He wouldn’t know a good story if it hit him in the face.”

Revision has negative connotations because many writers don’t know how to tackle that part of the writing process. It’s a shame because revision is the most important step. All writing is, or should be, revision. “It is at the center of the artist’s life,” Donald M. Murray writes in “The Craft of Revision,” “because through revising we learn what we know, what we know that we didn’t know we knew, what we didn’t know.”

When it comes to writing success, it’s the winning choice. Number 4 is the best choice. Successful writers recognize that revision is not failure, but another attempt to make their story better.

“What makes me happy is rewriting … It’s like cleaning house, getting rid of all the junk, getting things in the right order, tightening things up. I like the process of making writing neat.”

Ellen Goodman

For many writers, the problem is number 2 on the list. They don’t know how to revise. They know their story isn’t working, but don’t see a way out.

I know. I’ve been there and so have many of my students.

“I’m at the point in the process where I feel I have utterly failed,” one wrote me.. “(Not only that, I am a talentless hack and a fraud, etc. etc.). I can’t see what is wrong with the draft or how to fix it. Please send help.

I know how you feel, I wrote back, because I’ve been there, more times than I’d like to count, and will probably be in that place many times in the future — in the despairing trough of near-completion

I was able to offer her a solution, one I developed to help me move from draft to revision. It’s an 8-step revision strategy that I came up with as a way to push back the negative feelings I had about my draft.

I know it will sound mechanical and it is — deliberately so. At this point, writers are burned out, stressed. Their confidence has ebbed. I know this state of mind very well, and have learned that resorting to a mechanical process distracts me from my despair and forces my brain to come to my aid. It’s time to ditch the Muse and bring out the toolbox: a printer and a pen.

Writing is a journey that teaches us something new every step we take.

More than anything, revision demands distance. There are two types: temporal and physical. The first is time. When the novelist John Fowles finished a draft, he would put in his desk drawer, sometimes for months. (Try selling that to your editor!)

The other, more realistic approach, is the printout, a physical product separate from the screen where pixelated prose tends to look perfect.

To go the distance on a piece of writing, you need to separate yourself from it enough to see it with the eyes of a reader — a stranger to the text instead of the creator. In fact, you need to stop being the writer for a while and assume the role of reader.

Here’s the way that works for me.

1. Hit the print button. The first step in achieving distance is to change the medium. We see words on a page differently than those on my computer screen. A cognitive scientist could probably tell me why, but the fact remains. I find it easier to detect flaws and possible fixes on a printout than when I am staring at the electrons in front of me. Open the draft and hit print.

2. Listen up “The ear is a wonderful editor — and usually a much sharper, smarter and livelier editor than the eye,” says Stephen Koch in “The Modern Library’s Writing Workshop: A Guide to the Craft of Fiction.”

Read your story aloud, slowly, or, (my preference), ask someone to read it to you. During the reading, sit on your hands and keep your mouth shut; this means you can’t write on the draft or comment or respond, just listen.

Koch paints an unforgettable scene in the life of Charles Dickens. His daughter Mamie “was once granted the unique privilege of spending several days reading and resting on a sofa in her father’s very closed-door study while he worked.” Normally, nobody watched Dickens at work, but Mamie had been sick, “was her daddy’s darling,” and promised to keep still.

As a grown woman, Mamie recalled her father, oblivious to her presence, begin “talking rapidly in a low voice.” Even away from his desk, he would “whisper the emerging cadences aloud,” Koch says.

“Take it from the greatest,” Koch advises. “You will hear what’s right and wrong on your page before you see it.”

3. Mark up. Read the draft a second time aloud, or silently to yourself, but now every time something strikes you — a criticism, a question, a change — make a check mark at that point in the manuscript. Nothing more. You’re just recording a response to something in your story. It may be something you like, something that confuses you, something you’d change or delete, or move.

By now, your draft is getting messy, but that’s not a bad thing.

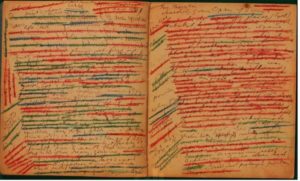

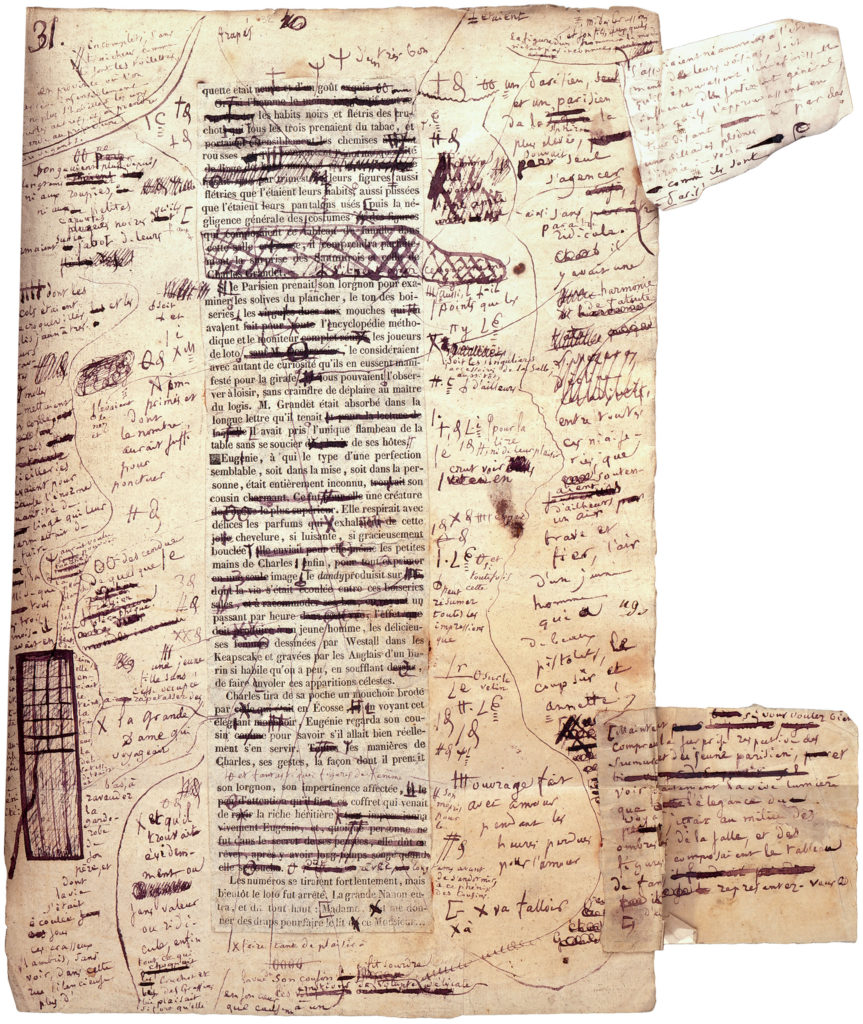

The sepia image, below, is a manuscript page written by Honoré_de_Balzac, the prolific 19th-century novelist who helped pioneer literary realism, the precursor of today’ narrative journalism.

Never satisfied with his work, he was still making changes even after he sent them to the printer, which was an expensive proposition. One of his stories reportedly underwent seventeen proofs. It may look like a chicken has had its claws dipped in black ink and sent skittering across that page, but as an inveterate reviser, I find the sight comforting.

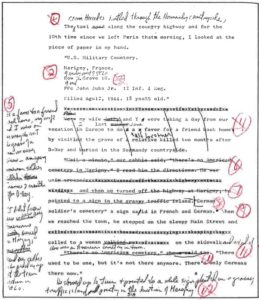

4. Countdown. Draw a circle next to every mark you’ve made. Number them. In the right margin, you’ll see an example of the method for a magazine story I was revising.

5. Remind yourself. Beside each number, write down why you flagged that word or passage. You will remember why you made the mark. For example, you might jot down, “cut this,” “check this with source,” “move this up,” “spelling,” “lead” or “kicker?” If the change is easy—deleting a word, correcting spelling, make it. Use arrows or slash marks to guide you.

6. Count up. Number the changes. Guesstimate how long each will take you to deal with each of them and write the number next to it. Five seconds. A minute. A half-hour of reporting. If you haven’t already guessed, I’m trying to make a game of it. Anything to keep me moving past the feelings of dread and despair a draft can inspire.

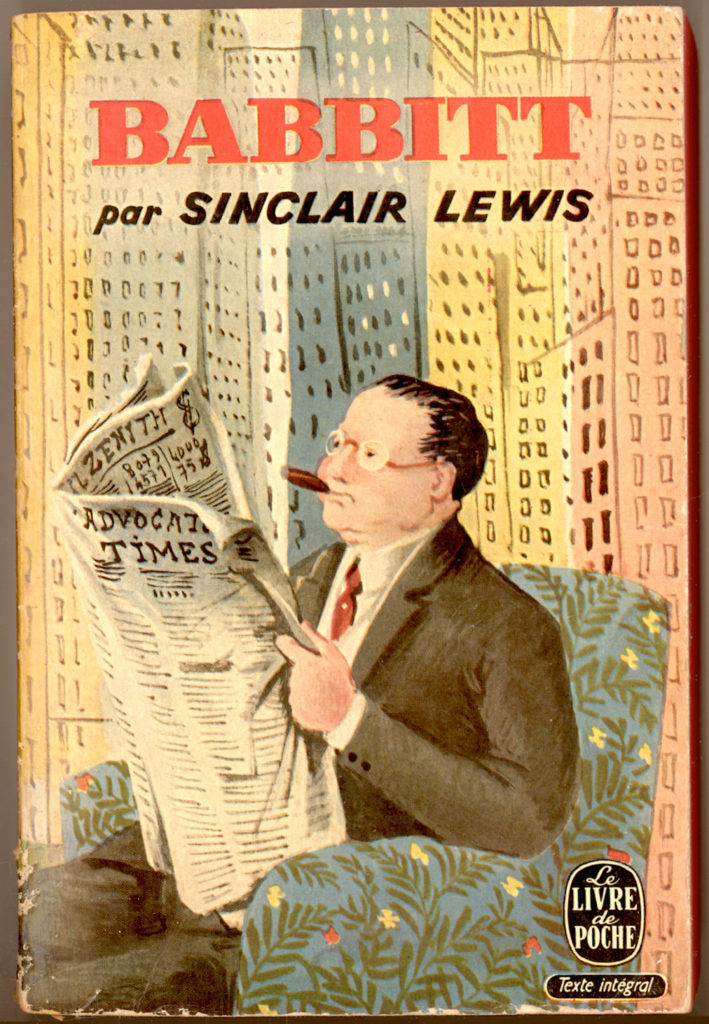

I love the flowers of afterthought.”

Bernard Malamud

7. Get moving. Place your marked-up draft by your screen. Open up the file and start revising. After every change, hit save (always hit save unless you use Google Docs and it does the job for you). Keep moving. Delete. Add. Cut and paste. X out each circle when you’re done. If you get bogged down on one, just skip over it and move on to the next. Move quickly. You don’t want to lose momentum. You may not be able to solve every problem in this revision. But you may the next time around, or, as I’ve found, the problem has been solved..

8. Rinse and repeat. Once you have gone through the entire list, hit print again. Repeat until you are satisfied, or you have to give up this story to your editor. While this method is especially helpful for long term stories, there’s no reason you can’t do it on a daily deadline. While this method is especially helpful for long term stories, there’s no reason you can’t do it on a daily deadline, especially when you leave time for revision instead of wasting precious minutes trying to craft the “perfect” lead. On very tight deadlines, I’ve managed to hit print once, read the story over for problems and make changes in 15-20 minutes You don’t have time not to.

This print, markup and revise method works because it helps furnish the psychic distance needed to address the problem you and many other writers face: I can’t see what is wrong with the draft or how to fix it.

Sometimes we can spot a problem in our writing without immediately knowing the solution. Some problems we may not be able to identify beyond a vague sense that “it’s just not working.” But we owe it to our stories to find out why. We must diagnose first if we have any hope of coming up with a good fix for the problem. And then fix it.

Sometimes we can spot a problem in our writing without immediately knowing the solution. Some problems we may not be able to identify beyond a vague sense that “it’s just not working.” But we owe it to our stories to find out why. We must diagnose first if we have any hope of coming up with a good fix for the problem.

I speak from experience. For many years, I would thrash around, bemoaning my inability to figure out why my story sucked and my powerlessness in coming up with ways to make it better. An experience several years ago with a short story changed my attitude. After producing multiple drafts, I still wasn’t satisfied but didn’t have a clue what was wrong or how to make it better.

I decided to give it one more read, marking up the manuscript whenever anything occurred to me as I read. I didn’t need to do anything more than make a checkmark or circle a sentence because when I read it again I remembered what it was that bothered me. (It was confusing, or repetitive, unclear, stilted, unnecessary) and in most cases I knew what to do about it; (rewrite it, move it, remove it).

When I was done and tallied up the marks I was horrified to see I’d come up with 113 things I thought needed to be fixed. And this for a 11-page story that had already undergone serious revision! (In fact, my wife and another writer friend had already told me to cut it out, stop obsessing, and send it off).

I decided to look at it as an exercise in revision: how long would it take me to make the changes. Okay, so it’s a head game, but at least it’s one I’m playing by myself.

It took me 2 hours and 45 minutes to make the changes. I read the new version aloud and when I got to the end I realized it was still not right. But now I saw, for the very first time, that the story actually ended three paragraphs earlier. I trimmed from the bottom, in the process ending with an exchange of dialogue that captured — and climaxed — the story in a way I’d never seen before. It was later published.

Every story can be a writing workshop, one that teaches us more about the craft. The lesson I learned is that even the most creative activity involves a certain amount of routine, even tedium. The woodworker spends hours hand-sanding a piece of furniture before applying the varnish that makes it gleam like a mirror. It may be tedious, but it’s a vital part of the process.

“Traveler there is no path,” the Spanish poet Antonio Machado says in an unforgettable line. “Paths are made by walking.”

May the writing go well.

Photo by Rebecca Matthews on Unsplash