William of Occam was a 14th century philospher, monk, and — few people realize — police reporter for the Occam News. (Okay, I made that last one up.)

He is remembered as the father of the medieval principle of parsimony, or economy, that advises anyone confronted with multiple explanations or models of a phenomenon to choose the simplest explanation first. Why Occam’s Razor? Because scientists use it every day or because it cuts through the fog of confusion are two explanations I’ve heard.

“If you hear hooves, think horses,” is one way to understand the principle. Or put another way, Keep it Simple, Stupid. K.I.S.S.

I didn’t know it at the time, but my introduction to Occam’s Razor came in my early 20s, when I was working for a crummy little newspaper and dreaming about becoming a writer, but doing more dreaming than writing,

A friend introduced me to a published writer. I asked her how I could become one, too.

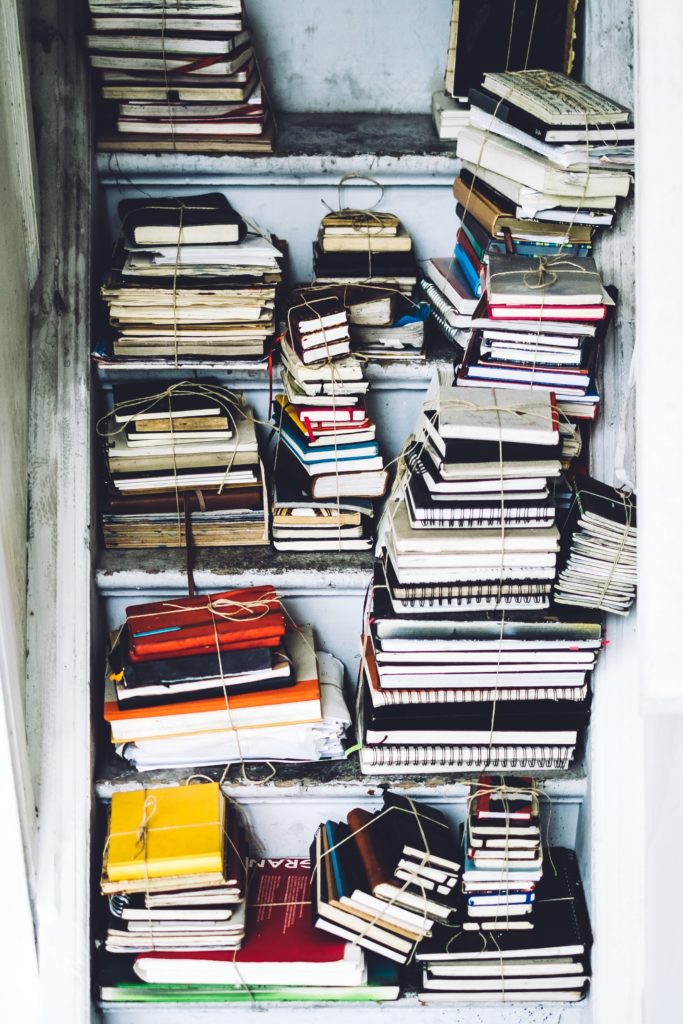

First, she said, you have to read all the time. Read everything — books, stories, newspapers, magazines. Everything. Read. Read. Read.

Okay, I nodded. What else?

You have to write, she said. All the time. Every day. Write. Write. Write.

I leaned forward expectantly, waiting to hear the rest of her advice.

That’s it, she said.

“Thanks a lot,” I remember thinking. “For nothing.”

I didn’t realize it at the time, but she was right. If you want to be a writer you have to read all the time and write all the time. It’s as simple as that.

Being a callow youth, I couldn’t accept it. There had to be more to it than that. Some magic formula.

But there really isn’t.

Want to write a story? Sit down and start writing. And then start revising.

Want to get published? Submit that story to a magazine or a literary journal. Write a novel or a screenplay. There’s no guarantee you will succeed, although it’s a safe bet that if you never try you won’t make it either. It’s that simple, and difficult, but well worth the challenge.

What many writers I meet seem to want and need is permission.

Can I do this? Can you do that? Is it okay to…?

My answer is always, yes. Yes, you can. It may suck, you may fail, you may get rejected, but the only way you’ll ever find out is by trying.

Want to write well? Follow George Orwell’s six rules from “Politics and the English Language.”

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Heed the prescription of “The Elements of Style” by Willian Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White. A sampling from the classic text:

- Make every word tell.

- Omit necessary words.

- Use parallel constructions on concepts that are parallel.

- Enclose parenthetic expressions between commas.

- Use definite, specific language

And finally the simple advice I try to heed for compelling writing.

- Use short words.

- Short paragraphs.

- Short sentences, but don’t be afraid to vary length for pacing and style.

- Go on a “to be” hunt,’ striking out passive instances of “is, was, was.” Replace with action verbs.

- Search “ly” for unnecessary adverbs.

- Trim bloated quotes.

- Spell checks. Cliche check.

- Read aloud.

- Research. Revise. Rewrite.

Looking back, I wish that writer had been more specific with her advice. Certainly, constant reading and writing and critical ae critical to becoming a writer. but there is so much more to becoming a published writer.

Like her counsel, some of this advice is obvious. But there’s a reason that scientists and other investigators continue to cite Occam’s Razor, more than 600 years after his death. It’s that simple.

Craft Query: What writing advice do you follow?

May the writing go well.

“Photograph by Josh Sorenson courtesy of unsplash.com