What’s the most important lesson you’ve learned as a writer

That it’s all about psychology . . . Yours, the reader’s, the characters’. As time passes, literature and psychology may well merge. Modern psychology grew from literature, after all; people forget that.

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

John Steinbeck once wrote that he’d held fire in his hands, and I figured it was his right to use any metaphor he damned well chose. Then, ten years later, I did a series of things right and, holy damn, I held fire in MY hands. I think it has to do with focusing a lot of human experience into a small number of words. Under certain circumstances, the writer as well as the reader can experience a momentary transcendence.

The point is that the magic is there, but reaching it requires a lot of technical skill as well as the inspirational kind. I had not really been expecting magic.

If you had to use a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be?

I’m a science person, in the end. That is, I believe in rationality. But my sciences are literature and psychology, both of which are close to my central interest, the human condition. After all, journalism can and frequently does become art.

All this is to say my own work is very science-like, but the universe it explores is literary. For example, I once used a computer program to pick out the overlapping rhythms of steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

But I think I like “naturalist”, to describe me and my work. Writing is part of the real world, and as such is subject to observation and experiment.

What’s the best piece of writing advice anyone ever gave you?

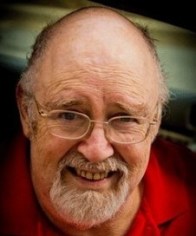

My first editor, G. Vern Blasdell, said that if you find the heart of a character and you’ll have your story; find the story, and it’ll point to your character. Sort of like yin and yang. Each is the backside of the other.

Vern also introduced me to the idea that modern literature is mainly a reiteration of the stories the Greeks told. Don’t look for a new story, you’ll fail. Find an ancient one in new clothes — they are everywhere, and they never wear out.

And then, of course, the only way you learn to write is liberal application of ass to chair.

Did you know about a condition known as writer’s ass? If you sit on your tail bone too long, the tiny vessels in your coccyx become occluded and die. The result hurts, aches, throbs, sometimes for decades and sometimes forever. That’s why Thomas Mann and Ernest Hemingway, among others, wrote standing up. I discovered that when I was diagnosed with it. Talk about hurt!

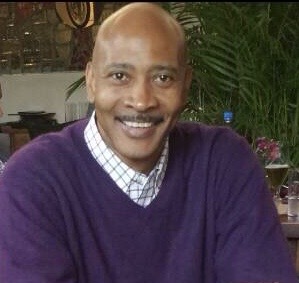

Jon Franklin is a pioneer in creative nonfiction. His innovative work in the use of literary techniques in the nonfiction short story, novel, and explanatory essay won him the first Pulitzer prizes ever awarded in the categories of feature writing (1979) and explanatory journalism (1985) for his work at The Baltimore Sun. His books include: “The Molecules of The Mind,” “Writing for Story,” “Guinea Pig Doctors,” (with J. Sutherland) “Not Quite a Miracle, (with Alan Doelp) and ” Shocktrauma, (with Alan Doelp). He spent eight years (1959-1967) as a journalist in the U.S. Navy, and, finally, as a staff writer for All Hands Magazine. He taught at the University of Maryland College of Journalism from and was then professor and chairman of the Department of Journalism at Oregon State University and director of the creative writing program at the University of Oregon before joining the Raleigh (NC0 News and Observer as a narrative writer, special assignments editor and writing coach. In 2001, Franklin returned to the University of Maryland as the first Merrill Chair in Journalism. He retired as an Emeritus Professor in 2010.