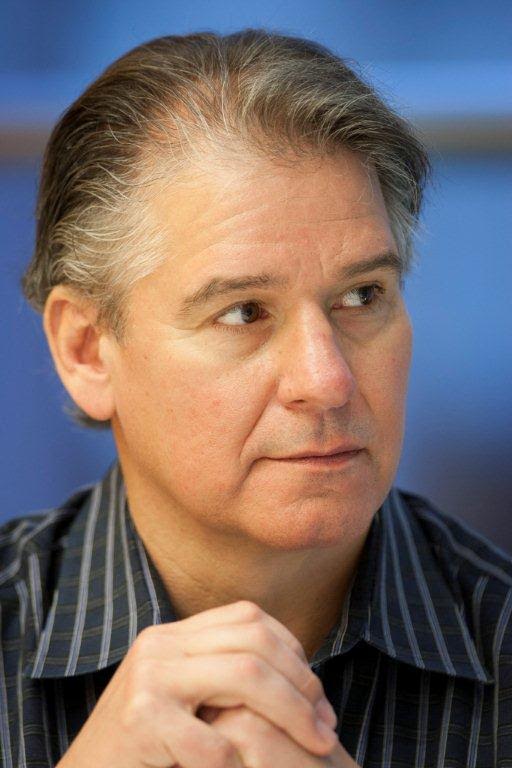

Last week, I posted the first part of an interview with Greg Borowski, longtime watchdog editor for The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. who every year for the last quarter century has written a short story keyed to the Christmas holidays.

His offering this year was “The Christmas Boxes,” a poignant story about a woman who connects with her dying mother suffering from dementia when she opens a box of Christmas decorations, each with their own memory.

Borowski’s yearly departure from nonfiction holds important lessons for writers ,whether they’re writing true stories or making them up as I learned when I interviewed him recently for Nieman Storyboard. Borowski is the author of “First and Long: A Black School, a White School and Their Season of Dreams.”

In this installment, he talks about whether writers of fiction need to report their stories, the differences and similarities between fiction and narrative nonfiction and the lessons nonfiction writers can learn from trying their hand at fiction.

Here’s the second part of our conversation, reprinted with permission.

You oversee projects and investigative stories? Do you hope the journalists you supervise will take inspiration for their own narratives from stories like this one?

I think writers get better by writing, but also by reading good writing. And good writing can be found in all sorts of places.

Inspiration can come from anywhere.

The key: Don’t read a great story and think “How could I ever do that?” Instead, approach it as: “How did they do that?” The former makes fiction seem like an unattainable form of art, the latter positions it as the craft it is.

We can all get better at our craft by practicing it.

The story is peppered with dialogue. How important is that?

I think the dialogue is vital. I usually start out with too much and realize some of what is being said should be part of an expository paragraph, and some is just extra words and does not belong at all. I find reading the dialogue aloud helps, and reading it quickly. That forces you to say it as you’d say it, not as it is written, which helps make it feel more authentic. In some respects, the dialogue is the most intimate part of a scene — you’re not just watching what is happening from afar, you’re listening to a conversation. So, a little bit can go a long way.

How does your work as a journalist influence the writing of this story?

Many of the same rules apply: Hook the reader with a strong lead — not just the lead at the start of the story, but the lead for each of the sections. Same goes for the endings. Provide hooks throughout that pull the reader along. Pare back your prose. Never be boring.

Really, the biggest advantage is the discipline any veteran reporter has to just get something on the screen to work with — and then rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, to polish your way to the strongest verbs and tightest sentences and crispest dialogue.

Good reporters know the stories that resonate most with readers are the ones that speak to deeper themes and ideas. You always have to be able to answer the question: “What is the story about?”

In this case, you can answer it by saying it is a story about a woman who dies on Christmas Eve and her estranged daughter who arrives at her bedside.

Or you can answer that it’s a story about: Loss. Forgiveness. Memory. Love.

The first answer — the plot — is just a means to illuminate the second, the theme.

Did you draw anything in the story from life?

Lots of things. Part of the original concept came from the experience with my late grandmother. Like the character, her name was Susan; her husband was Leonard. As a kid, I used to get tasked with helping my grandmother make ornaments — those kits that require precise beads and sequins. And, yes, she got to press the pins in while I put the beads on in the right order.

The living room belongs to a great aunt, though there were plastic runners on the floor instead of plastic on the couch. I remember visits as a kid where it seemed like there was nothing you were allowed to touch. The trio of ceramic angels were heirlooms on my mother’s side, though I got one of the instruments wrong. (Why would angels have cymbals?).

Usually, I tuck in the names of nieces or nephews, or children of friends. My daughter, Annaliese, is in every story — not by name, but usually a referenced age or, in this story the sixth-grade.

I don’t write the stories from life, but there are always pieces of life in the stories.

The story is full of textbook examples demonstrating the power of show don’t tell. Instead of saying her soldier father died, perhaps in a war, you write, “On the end table was a photo of her father, his Army uniform ever pressed, his smile ever easy, his eyes ever bright. Lauren had never met him — she came along three months after he passed — but knew the story well: Her mother was expecting a Christmas Eve phone call, but got a knock on the door instead. The flag, precisely folded, was in a case on the mantel.” Why did you compose it this way?

One practical thing that has strengthened my stories, I think, is the need to keep them short enough to be printed out with Christmas cards. They must fit on a piece of legal paper, landscape mode, four columns of text on each side. This enforces some discipline on the process, and requires me to develop sharp themes and crisp scenes.

The paragraph you cite is typical of at least a few that come up each year, where I need to tell a lot in a few words. Here I was trying to describe the living room, give a backstory for the characters and encapsulate the conflict that needs resolution. At the same time, I wanted to convey a feeling of wistfulness.

Do you think journalists should try their hand at fiction?

Yes. I think writers of all stripes only get better when they try new things and push their own envelopes. Likewise, writers of fiction would probably learn a lot by trying their hand at narrative nonfiction, as it would force them to work on a different set of related skills.

In recent years, I have become a runner and know you don’t get better just by running. You have to do cross-training, too, to strengthen different muscles. The same applies here.

You can read the entire story here.