What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned as a writer?

I saw that Dan Barry said that a big lesson for him was that the process gets harder. That feels true. But for me the process has gotten easier. I am not Sisyphus kicking that stone downhill. But I feel that I am at least rolling it on a level plain. But it only gets easier if you are willing to relearn the big lessons with each project. I’m talking about books now. I’ve written six in twelve years. I have a process that I borrowed from Bill Howarth’s description of John McPhee. I need my raw material, my index cards, my file folders, my bulletin board. If I try a shortcut, if I lean too heavily on my experience, if I try to dance over a step, I usually crash to the bottom of the staircase. Use the process. Follow the steps. Trust the process. You have to trust. Even if it’s not going well at this moment, keep at it. Realize that the imperfection you feel right now is necessary. There was a great bowler from Texas named Billy Welu who used to be a color commentator for televised bowling tournaments. He would point out that some bowlers with big hooks needed to roll the ball at the edge of the gutter in order for it to curve into the pocket for a strike. “Trust is a must,” he would say in a Texas drawl, “or your game is a bust.”

What’s been the biggest surprise of your writing life?

My biggest surprise as a writer came when I was about 30 years old. It surprised me again when I was about 60 years old. This had to do with my personal and professional identity. That is, how I identified myself. I meet people all the time who say, “I’m not a writer, but I am working on a novel.” Or “I write reports at work all day, but I’m not saying I’m a writer.” I play rock and roll piano. And on occasion I hit a golf ball. I am not Jimi Hendrix or Tiger Woods, but I feel comfortable calling myself a musician and a golfer. I was trained in graduate school to become a young English professor. And I wrote a Ph.D. dissertation about Chaucer, but I did not consider myself a writer. I became a newspaper writing coach, but did not call myself a writer. In 1979 I had about 250 bylines in the St. Petersburg Times. Finally, it hit me: “You know, Roy, maybe you could be a writer.” It feels crazy in retrospect: becoming a writing coach BEFORE I embraced the identity as a writer. Thirty years later, I could easily say I was a writer and a teacher of writing. Then it happened again. I wrote the book “Writing Tools” – followed by five more with Little, Brown. LB published Emily Dickinson! “Holy shit,” I thought, “I’m not just a writer – I’m an author!” If you write, you’re a writer. If you auth, you’re an author.

If you had to choose a metaphor to describe yourself as a writer, what would it be?

I am fascinated by the work of Phoukhoun Phimsthasak, a woman who made her way from Laos to America. She has an amazing personal story of escape, rescue, renewal, and hard, hard work. My wife and I know her as Jane. She does manicures and pedicures. As I metaphor, I can think of myself as a nail specialist. I work with an elaborate tool set, and a process that has a set of predictable steps, with some special challenges and surprises along the way. My mission relates to both utility and beauty, but also to listening and public service. It’s also about relationship building and referral, because there are a lot of nail specialists out there and many of them are good. But I want you to keep coming back to me.

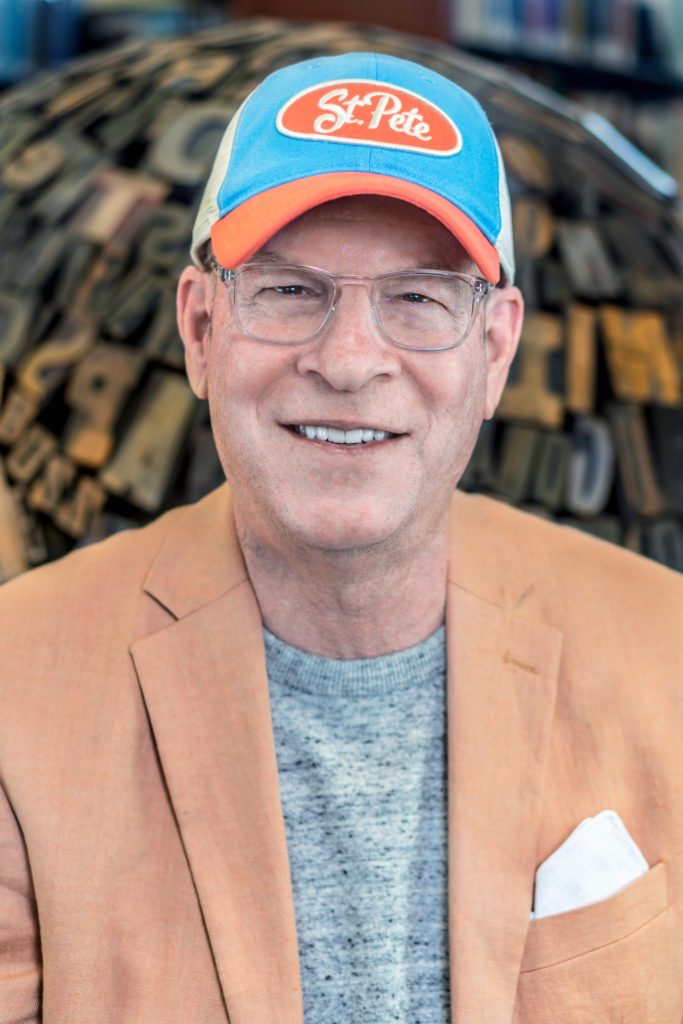

Roy Peter Clark is senior scholar at the Poynter Institute. He has taught writing at every level — to schoolchildren and Pulitzer Prize- winning authors — for more than forty years. A writer who teaches and a teacher who writes, he has written or edited 19 books, including “Writing Tools”, “The Glamour of Grammar, “”Help! for Writers,” “How to Write Short,” and “The Art of X-Ray Reading.” His latest — a writing book about writing books — is due out in January: “Murder Your Darlings: And Other Gentle Writing Advice from Aristotle to Zinsser.” He lives in St. Petersburg, Florida, hits a golf ball now and then, and plays keyboard in a blues band .